Hot Coffee Conversation with Georgian art historian Mzia Chikhradze

Published Wednesday, October 1, 2025

I met the distinguished academic, researcher, and pedagogue Mzia Chikhrardze over the summer in New York. We went to MoMA, where we discussed intricate details of Georgian Modernism and what issues the country is facing when constructing a comprehensive art historical narrative of the 20th and 21st centuries. This printed conversation is below. Mzia Chikhradze (მზია ჩიხრაძე) graduated from the faculty of Art History and Theory at the Tbilisi State University. In 2006, she was awarded a Doctor of Arts degree. Since 1988, she has worked as a Senior Researcher at the G. Chubinashvili National Research Center for Georgian Art History and Heritage Preservation. From 2006 to 2007, she was a Visiting Scholar at Yale University (United States), and in 2008, as part of the Open Society Institute’s Faculty Development Fellowship program, she became a Visiting Scientific Fellow of the Harriman Institute at Columbia University in New York. She is also a former participant of the Fulbright Scientific Research Program in the United States (2009-2010). Mzia Chikhradze taught art history at the Tbilisi 1st Experimental School, the Tbilisi Institute of Foreign Languages, and the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts. She was an Associate Professor at the IB Euro-Caucasian University. From 2014 to 2016, Chikhradze served as an Invited Professor at the Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, in the Faculty of Humanities, the Educational Scientific Institute of Art History and Theory. Between 2011 and 2013, Mzia Chikhradze was a Visiting Professor at Columbia University in New York, where she taught the course “Modernism on the Periphery of Europe: Georgian Modernism at the Crossroads of Cultures.” She currently teaches visual arts at the IB European School (program: Diploma in Visual Arts). Since 2015, she has worked as an Invited Professor at the Free University‘s Visual Arts and Design School. Mzia Chikhradze has participated in many international conferences and scientific programs, including the research project of the Fundamental Research Program of the Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation Integration and Identity (as Project Leader, 2016-2019). She currently teaches at The School of Visual Art and Design (VADS) at Free University of Tbilisi.

Nina: Imagine you are in your favorite coffee or tea spot. Where is it? What are you drinking? What are the three things you see right now?

Mzia Chikhardze: It’s in Paris, at the legendary literary café “Les Deux Magots.” I’m sipping a fragrant cup of tea while savoring a slice of warm, golden Tarte Tatin. I see the elegant interior of the café glowing with history, an imposing waiter moving gracefully toward me, and the two Magot statues perched high on a pillar above, silently watching over it all.

Tarte Tatin, image courtesy of BBC.

Nina: As a distinguished art historian and pedagogue in Georgia, what would you say are the main issues or concerns for developing the contemporary art scene? And what are the main challenges you are facing as an art historian who has been consistently researching the main transformations of the 20th-century Georgian culture?

MC: I think "distinguished" is a bit of an overstatement, though I do have substantial experience as both a scholar and a teacher. My research extends beyond contemporary art to include historical analysis, questions of cultural inheritance, and an exploration of their influence on current artistic practices. The development of the Georgian contemporary art scene requires a complex, multifaceted assessment. A closer look reveals numerous obstacles that can be broadly categorized into practical and theoretical problems.

Practical Problems are:

Institutional Deficiencies - Georgia lacks a dedicated Museum of Contemporary Art that could present ongoing artistic processes in both local and international contexts. Similarly, the number of galleries focused on contemporary art remains very limited. State support is inconsistent, fragmented, and unsystematic, with no coherent cultural policy in place;

International Integration - Opportunities for Georgian artists and curators to engage internationally are scarce. The country lacks residencies, biennials, and collaborative platforms that would facilitate integration into the global art scene;

Education and Critical Discourse - Public and academic knowledge of contemporary art remains minimal. Critical analysis of contemporary artistic practices is almost absent, and no platform exists for sustained academic or critical discussion. This lack of engagement often leads to misunderstanding and rejection of contemporary art;

Limited Commercial Environment - Due to low incomes and the absence of sponsorship from business sectors, artists rarely have the means to finance exhibitions abroad or participate in international projects. The lack of cultural policy further restricts the commercial viability of contemporary art in Georgia.

Theoretical and Research Problems are:

Fragmented Research Resources - While access to literature and research materials on contemporary art has improved, it often depends on personal connections and study abroad. Locally, documents, manuscripts, and archives remain scattered, with little effort to digitize or centralize them for scholarly use;

Absence of a Unified Narrative - There is no comprehensive account or historical-artistic assessment of Georgian modernism and contemporary art. The absence of such a framework prevents the identification of deeper roots and limits a coherent understanding of current developments;

Terminological and Conceptual Challenges - A major barrier in contemporary art criticism is the lack of clear terminology and a robust theoretical foundation. Without a systematic interpretive framework, explaining contemporary art in a language accessible to both specialists and the wider public remains difficult.

The list could be expanded much more, but shortly, the challenges hindering the development of Georgian contemporary art are both structural and intellectual. Addressing institutional gaps, fostering international integration, strengthening education and critical discourse, and building a solid theoretical base are essential steps toward establishing a more sustainable and globally relevant art scene.

Nina: Please tell us about Integration and Identity: Georgian Artists Abroad - a database you have been working on from 2017 to 2019 under the auspices of the Institute of Art History and Theory of Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, and was funded within the Fundamental Research Grant Program of Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation? What was your research method? How did you choose your respondents? Did you come to any conclusions?

MC: As I already mentioned, there is a big issue of consistent and complete analysis of the history and theory of Georgian modern and contemporary art in Georgian art criticism.

In 2016, the group of scholars, including myself as principal investigator, together with the art historians Ketevan Shavgulidze, Mariam Shergelashvili, Marita Sakhltkhutsishvili, and Lana Karaia, began the project Integration and Identity. The goal was not only the creation of a database, but also to conduct an interdisciplinary study of the work of Georgian artists who migrated and worked abroad, which had previously remained outside the realm of scientific research.

The topic in itself is of an acute actuality, as on one hand this phenomenon of Georgian art is still the arcane field of study and on the other hand, the role of Georgian émigré artists is immense in contributing to cultural integration of Georgia with the western culture and vice versa, i.e. in enriching and diversifying local art scene with the artistic values transmitted from the west.

In order to define the current form of contemporary Georgian visual art, to reveal the creative potential of Georgian artists and to analyze the ways of its development, it is necessary to present to the general public one very important creative segment - the life and work of Georgian contemporary artists who have migrated abroad. This group of artists is a bearer of the diversity of cultural self-expression and largely determines the current form of modern Georgian art. This phenomenon essentially determines the cultural integration of Georgia with the West and, at the same time, enriches the local artistic space with different artistic values that have come from the West.

The professional careers and creativity of the artists participating in our research were formed in the West and are part of the international art space, but modern Georgian art is also created through these authors. Moreover, an assessment of the current state of contemporary Georgian art without taking into account the experience of these artists is incomplete. In this regard, not only their professional and artistic activities are important, but also the value aspects of these artrists, their worldviews and social experience. We had only fragmentary, often accidental information on all of the above. Therefore, as a result of interdisciplinary research, lists of Georgian emigrant artists were established, their location was determined, their works were recorded, and the characteristics that the creativity of Georgian artists acquired during integration with Western culture were revealed. It was determined what contemporary trends enriched the latest Georgian art, what form such artistic and cultural exchange ultimately took.

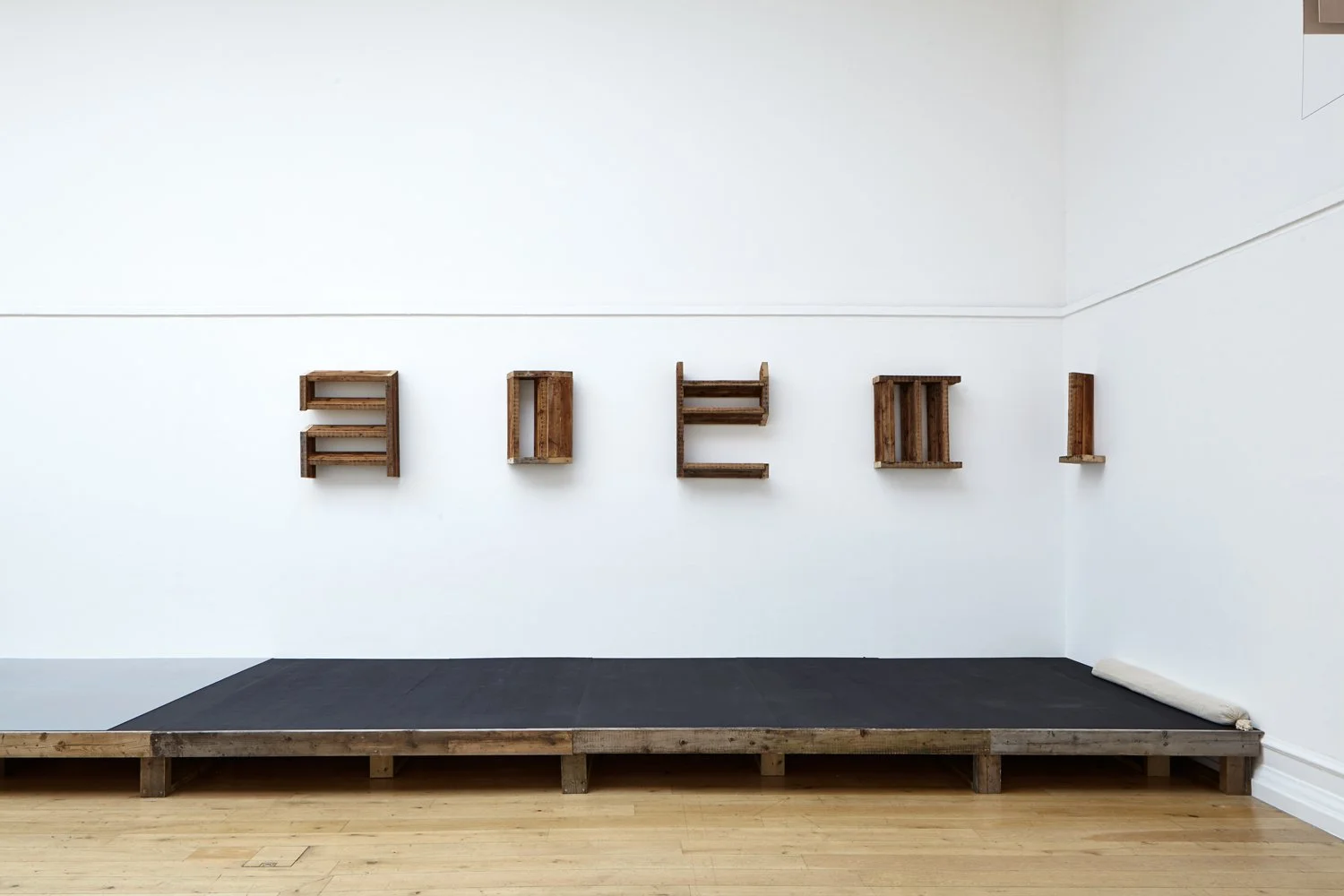

The study focused on those Georgian artists who have achieved success and are today quite important actors in the contemporary art scene. These are: Tea Jorjadze, Luka Lasareishvili, Andro Vekua, Lado Pochkhua, Levan Mindiashvili, Eter Chkadua, Gia Edzgveradze, Anna K.E., Tea Gvetadze and others. At the same time, we analyzed the art of those artists who have not, or have not yet, achieved this status. Overall, we evaluated the work of immigrant artists from an art-historical, artistic-aesthetic and their value-worldview point and determined what factors shaped the degree of their success/failure.

The role of immigrant artists in the development and history of Georgian contemporary art was determined, and it was revealed how important role these artists play in Georgia’s cultural integration with the West. Based on this interdisciplinary research, an electronic database was created, and scientific findings were combined into a collection of scholary works.

The following research methods were used in the research process: art history research method, comparative method, archival research, scientific and theoretical analysis of works of art. Also, one of the most important parts of the research is a sociological survey-analysis, through which the main research material was collected and processed.

The diverse kaleidoscope of Georgian artists is synthetically inscribed in the complex landscape of contemporary art. Their art intersects with the space where painting, sculpture, photography, installation, film, video, performance, Internet art and works that do not belong to any specific category coexist. The diversity of the problematics of their art is also in line with the themes that other contemporary artists working in the West today are grappling with. The scope of these problems is wide: feminine or feminist, gender themes, sexual and national minorities, fluid identities, displacement, displacement, political, social problems, identity, cultural past and place, the relationship between man and nature, the inner duality of the personality, what is hidden in the subconscious, and more. Their forms of visualization and creative expression are also pluralistic, where replica, commentary, quotation, metaphor, reproduction, the multi-layeredness of texts, the confusion of the fictional and the real, the illusory and the real, the past and the present, create a field of blurring the boundaries of perception and multiple meanings, of unstable identification, where nothing is precise, and the space is wide open for subjective reading. It should be said here that the national form, foreign to postmodernist culture, has also been erased among Georgian immigrant artists. From a visual-formal point of view, their art is international, global, but the identity, experience, values, feelings, pain, and even trauma encoded in the visual-artistic forms and images they create come from territorial-historical and cultural ties, which often determine the thematic or emotional inspiration of these artists' work.

Installation view of Thea Djordjadze's Ma Sa i a ly e a se – de, 2015 on view in the Main Galleries. Courtesy Sprüth Magers. Photo: Andy Stagg.

Nina: I wanted to ask you about your article "Gesture of Thoughts: Immigrant Georgian Artists in the U.S." In it, you mentioned that "Emphasizing the national in an integrated artistic space only becomes important if the artistic approach based on it touches on a common global socio-political or philosophical context. Locally, it is possible to talk about the origin of this or that artist only in a biographical or historical aspect.” Can you please elaborate on this statement? As you have lived in New York before and know its multicultural artistic narratives, it is valuable to learn more.

MC: Today’s contemporary art scene is marked by chaotic and eclectic developments. Critical thinking and analytical assessment are essential for artists to avoid producing superficial, imitative, or exoticized work. To navigate this, Georgian artists often engage deeply with their national heritage, seeking to reconcile it with universal artistic values. The vast majority of Georgian artists who have emigrated carry this cultural trace in their hearts; Georgia remains a source of inspiration and research for them. Working in a foreign context, these artists search for a unique artistic language and identity. Their personal visual language reflects individual experiences, insights, and responses to events. Such specificity is crucial for migrant artists: it allows them to assert a distinct voice in the Western art world while preserving traces of their cultural origins.

Although national forms may seem alien to postmodern cosmopolitan culture, Georgian immigrant artists often merge seamlessly into the diversity of Western modern art. Visually and formally, their work may appear global and international. Yet the identity, values, emotions, and even trauma embedded in their work are rooted in their territorial, historical, and cultural ties, shaping both the themes and emotional resonance of their art.

This dynamic is particularly evident in New York, the unquestioned global center of contemporary art, where the panorama of 21st-century art unfolds. In this complex landscape, Georgian immigrant artists navigate and respond to a multiplicity of artistic languages and issues. Their forms of expression are pluralistic: they incorporate replication, commentary, quotation, metaphor, layering of texts, and the blurring of fiction and reality, past and present. This creates a field of unstable identification and multiple meanings, leaving space for subjective interpretation.

For many of these artists, there is no longer a “stylistic imperative” (Arthur Danto). Art no longer requires a clearly identifiable form; the philosophical content of a work can alone define it as art. This aligns with another hallmark of contemporary art, especially visible on the New York scene: diversity and multiplicity, characteristic of postmodernism.

The central question, then, is the role of post-Soviet Georgian artists in this postmodern—and perhaps post-postmodern—cultural cycle. How have they found their place in American art? How have their historical and personal experiences, shaped by Georgia’s recent political, social, and cultural history, been transformed and integrated into their work? To what extent have they freed themselves from Soviet legacies embedded in memory or cultural inheritance? And ultimately, has their art become an original, organic part of American artistic and cultural life? Our research addresses these questions.

Nina: Another important article of yours delves into Georgian modernism during the time of the Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918-1921). As we touched a little bit on this in our exchanges, I was wondering what role female artists play in those years of transition when the Republic was defeated in Georgia and the Soviet regime was taking over the country. Whose names would you single out?

MC: Those were very difficult times for Georgia. The Democratic Republic had lost its independence, and modernist artists came under increasing pressure from Soviet ideology. Women artists were very much part of these processes, actively participating in both artistic and cultural life. I would particularly highlight Elene Akhvlediani, Ketevan Magalashvili, and Ema Lalaeva.

Magalashvili and Akhvlediani were both sent to Paris to advance their artistic training. They both returned to Georgia in the second half of the 1920s. Ketevan Magalashvili worked at the Georgian Museum and was a close friend and collaborator of Dimitri Shevardnadze, the artist and cultural figure who established the museum and many other art institutions. His arrest and execution in 1937 left a deep mark on her—she withdrew from public life for a long time, though she continued to work as a painter until she died in 1973. She was well-known for her impressive portraits.

Elene Akhvlediani, regarded as a pioneer of urban landscape painting in Georgian modernism, returned from Paris and, in 1928, began collaborating with the theatre director Kote Marjanishvili, the founder of the modern Georgian theatre. In the late 1920s and 1930s, Akhvlediani carried her avant-garde experiments into stage design, which may have been a way to survive the strict censorship of the time, as she was closely monitored after her studies abroad. Under these pressures, her art gradually shifted from avant-garde approaches to more realist landscapes. Beyond her artistic innovation, Akhvlediani also created a circle of women painters who worked together, often holding plein-air sessions. These gatherings were not only opportunities for experimentation and exchange but also an important space for promoting women’s art and preparing younger artists for public exhibitions.

Emma Lalaeva-Ediberidze, an Armenian-origin artist from Tbilisi, was considered the most “leftist” artist in Georgian modernism. She explored Futurism, Cubo-Futurism, Rayonism, and Constructivism in her graphic works and theatre designs. Like many of her colleagues, she was not spared from Soviet repression—her husband was executed in 1937, and she herself was expelled from the Academy of Arts.

All three female artists were affected by the Soviet regime in different but quite powerful ways, which, of course, left a specific mark on each of their lives and art.

Ketevan Magalashvili, Portrait of Dimitri Shevardnadze,1921.