Hot Coffee Conversation with Abigail Klem Spector, Warren Spector, and Glenn Adamson on the Launch of the Spector Craft Prize

Published Friday, November 14, 2025

A new exciting initiative has been presented this week. On November 11th, the Spector Family Foundation, together with celebrated curator Glenn Adamson the announced the launch of the Spector Craft Prize and an inaugural partnership with Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. The Spector Craft Prize is a transformative new initiative that seeks to reinforce American craft as a vital and enduring art form and nurture new generations of craft artists and makers. Created by Abigail Klem Spector and Warren Spector, the Prize celebrates craft as a dynamic force in contemporary culture—one whose preservation is critical to the American creative tradition—and looks to establish a recognized platform for excellence across disciplines, including ceramics, woodworking, glass, textiles, metalwork, paper arts, basketry, and more. The announcement of this new and timely prize is a perfect reason for an interview with Abigail, Glenn, and Warren.

Nina: Imagine you are in your favorite coffee or tea spot. Where is it? What are you drinking? What are the three things you see right now?

Abigail: My favorite coffee spot is actually in the morning, in bed, before anyone else is up. It’s my quiet time. Well, technically, Warren is up — he makes the coffee, which might be the best part. It’s a double espresso, and I spend about half an hour with it before the day begins, looking at my beautiful de Gournay wallpaper and my dog, reading the newspaper, and easing into the day in a calm, reflective way.

Warren: You’ll notice that Abigail said “quiet time” at least three times. I’ve learned that my job is to deliver the coffee — silently. It took me a while to figure that out. I used to sit at the end of the bed and ask, “How are you? What’s the plan for today?” until I realized that’s not what she had in mind.

I drink English breakfast tea made with loose leaves from McNulty’s. My favorite spot is on our back deck on Martha’s Vineyard, overlooking the water. We have a beautiful table there by Ido Yoshimoto, a Northern California woodworker whose pieces are extraordinary. I sit there watching the ospreys dive for fish — it’s serene and grounding.

Glenn: I’m not in my favorite spot right now — I’m in London — but it would definitely be my house in the Hudson Valley. Honestly, anywhere in the house is fine as long as I have the right mug: one I bought while working at The Clay Pot in Brooklyn back in 1994. It’s by the potter Ellen Shankin, and I still use it 30 years later. I like to sit quietly, look out at the trees and the birds, maybe put on a bit of classical music — much like Abigail, I start the day with calm and reflection.

Portrait of Abigail Klem Spector by Shana Trajanoska.

Nina: The Spector Craft Prize launched this week, November 11, with its first call for entries. Why now? And how will the selection process work?

Abigail: The timing feels both personal and timely. What began as a personal project — creating a home filled with meaning — evolved into something much larger. As I sought handcrafted pieces for our home, I discovered this incredible community of artisans around New York City. In getting to know them, I became aware of both their immense talent and the challenges they face. That discovery inspired me to learn more and to find a way to give back — which led me to Glenn, and to the idea of doing something meaningful for the craft community.

There’s also a broader cultural context. In a world increasingly shaped by technology and AI, people are yearning for connection, for community, and for the handmade. These forces — the desire to support artisans and the search for balance in our digital age — came together to shape this initiative.

There’s also an urgency: during studio visits, we often felt that without active support, vital knowledge could be lost. That’s why mentorship and visibility are at the heart of this prize — preserving craft traditions while fostering intergenerational dialogue. Craft is a living practice, and this prize aims to help sustain that continuum.

Warren: I completely agree. The more digital our world becomes, the more we crave tangible connection — with people, with objects, with place. Whether it’s local food or handmade work, these things root us in something real.

Glenn: I love what Abigail said about “creating a house full of meaning.” That sentiment really captures the spirit of this whole project. As Warren said, connection is key — but not the social media kind. We’re talking about deep, personal, enduring connections, the kind that often grow through mentorship.

Craft, historically, has always involved this transmission of knowledge — the master-apprentice relationship — and we wanted to reimagine that for today. That’s why the prize includes both the main Spector Craft Prize and the Emerging Artist category: to celebrate craft as a lifelong pursuit, where tradition and innovation coexist and evolve.

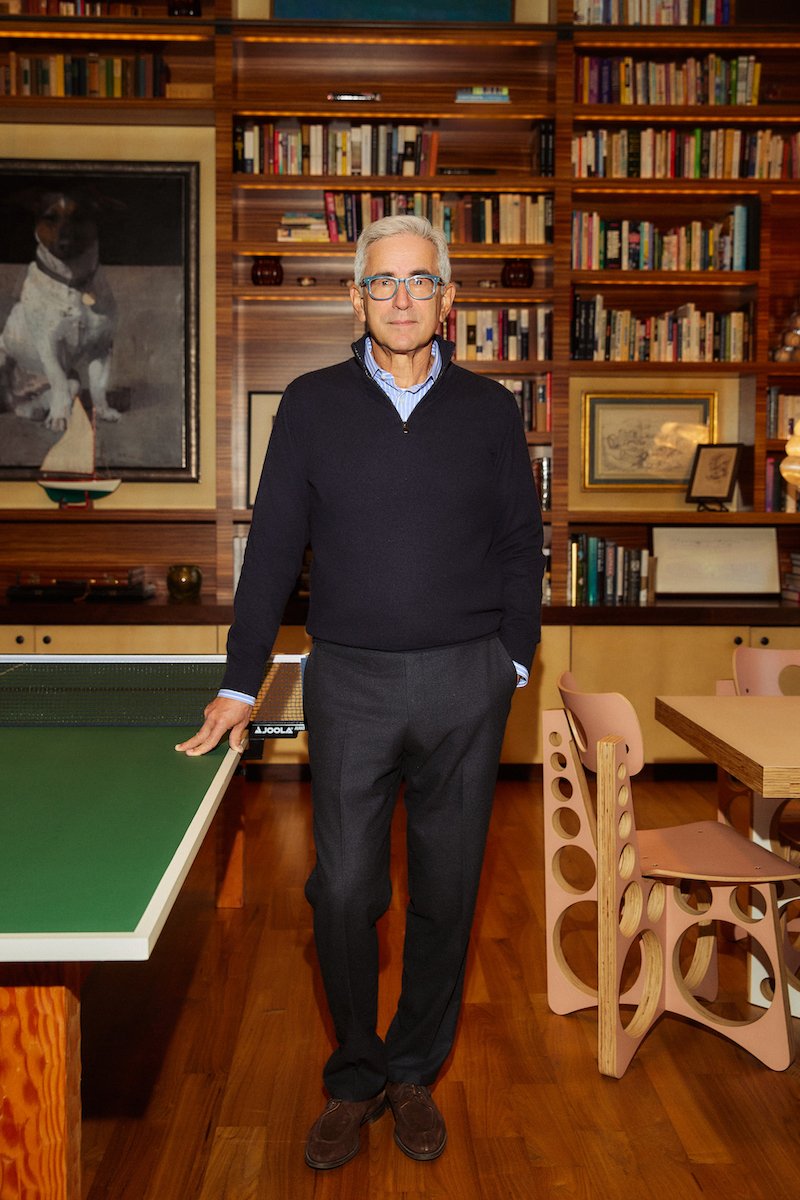

Portrait of Warren Spector by Shana Trajanoska.

Nina: How will the winners be recognized, and how do you see your partnerships with institutions developing?

Warren: We’ve structured the program around two awards: the Spector Craft Prize and the Spector Craft Prize for Emerging Artists.

For the main prize, artists won’t apply directly. Instead, our Advisory Board and the curator from the host museum will nominate artists for consideration. The host museum will change each year, and we’re thrilled to begin with Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas.

Together with Crystal Bridges, we’ll select an artist whose work both the museum and our foundation wish to celebrate. We’ll acquire a major work from the winner, to be donated to the museum’s permanent collection, where it will be displayed. The winner will also speak at the museum’s annual Summit and help select the next year’s emerging artists.

For the Emerging Artist Prize, the open call starts this week and runs until March 1. Artists can apply through our website. We’re hoping for a broad, diverse group — different media, backgrounds, and regions. After an initial review, our jury, chaired by Glenn, will select five winners.

Each winner will receive $10,000, mentorship, and professional development opportunities, and they’ll be invited to the Crystal Bridges Summit next November. It’s about supporting these artists, expanding their reach, and building lasting networks.

Glenn: The choice of Crystal Bridges was very deliberate. We’re looking for institutional partners with a genuine commitment to craft. Crystal Bridges is an outstanding example — they recently received a major grant from the Wingate Foundation to fund a full-time craft curator, and they’re building an impressive collection. They’ve become a national leader in this field, making them a perfect inaugural partner.

Portrait of Glenn Adamson by Shana Trajanoska.

Nina: What qualities will you be looking for in applicants? Originality?

Glenn: Our website outlines the criteria, but if I had to distill it into one phrase, it would be “the transformation of tradition through innovation.” Craft is a living, evolving practice — it carries forward generations of accumulated material intelligence. The artists we’re drawn to understand their medium deeply, but also push it forward expressively. When you encounter their work, you feel the maker’s presence.

Roberto Lugo, who’s on our jury, embodies this beautifully. When you stand in front of his work, you feel his energy — his story — radiating from it.

Warren: For the main prize, we’re also looking for artists who engage in mentorship or community work. We value those who not only excel at their craft but also contribute to its future — people who nurture the next generation and sustain the field.

Crystal Bridges Museum, courtesy of DADA Goldberg.

Nina: Will there be any age restrictions?

Warren: Not exactly. The main prize will generally focus on mid-career artists, but that’s not a strict rule. The Emerging Artist category is open to those who’ve been practicing for seven years or fewer — regardless of age. Someone who began a craft practice later in life would be equally eligible.

Roberto Lugo Teapots at the Spector Home. Image courtesy of the Spector Family Foundation.

Nina: Do you plan to expand internationally in the future?

Abigail: Our focus is on artists living and working in the United States. We feel strongly about supporting American craft and its connection to our cultural identity and heritage.

There are already wonderful international prizes — the Loewe Craft Prize, for example, has been a great inspiration to us — but we wanted to create something that celebrates and sustains American makers. That’s a big enough mission on its own.

Roberto Lugo Vessel at the Spector Home. Image courtesy of the Spector Family Foundation.

Nina: What first drew you each to craft?

Abigail: I spent many years in fashion, so I’ve always been drawn to things made by hand. But my deeper connection came when I was creating a new home for my family. I became acutely aware of the meaning embedded in handmade work — how it carries intention and humanity in a way that mass-produced objects simply don’t.

Warren: My interest started through collecting. Before Abigail and I met, I focused mostly on Arts and Crafts and early 20th-century work. I was captivated by the craftsmanship and the philosophy behind it, which, interestingly, was a reaction to industrialization, much like what we’re experiencing today.

When Abigail and I began collecting contemporary craft, we realized how different it was to engage directly with living artists. Visiting studios, meeting the makers — that personal connection was transformative.

Glenn: My own “origin story” goes back to college, when I was studying Chinese ceramics. I was allowed to handle a group of medieval pieces, and I remember feeling an almost electric connection — like I’d found my intellectual home. Compared to studying slides in a dark lecture hall, holding those objects was revelatory. That moment lit the spark for everything that followed.

Wishbone Chair by Art Carpenter, courtesy of Glenn Adamson.

Nina: What’s your favorite piece of craft from your personal collection, and why?

Abigail: We’ve talked a bit about Roberto Lugo — his work was my most visceral emotional reaction to craft. Seeing how he reimagines traditional forms through the lens of his own story moved me deeply. Each of his vessels tells a narrative, and collecting them has been profoundly meaningful.

Warren: It’s hard to pick one, but I’ll go with a recent acquisition by Liz Collins — a textile piece called Pathways. It hangs on the wall like a painting, and at first glance, people don’t even realize it’s a textile. It’s electrifying, literally and figuratively, and it makes me smile every time I walk by it.

Glenn: For me, it’s a chair by Art Carpenter — yes, that’s his real name — called the Wishbone Chair, made of California walnut in 1969. I bought it in graduate school, and it’s been with me ever since. The form itself feels almost magical, like its name. I sit in it when I write, usually with my coffee, in my Hudson Valley home.

Group portrait by Shana Trajanoska.