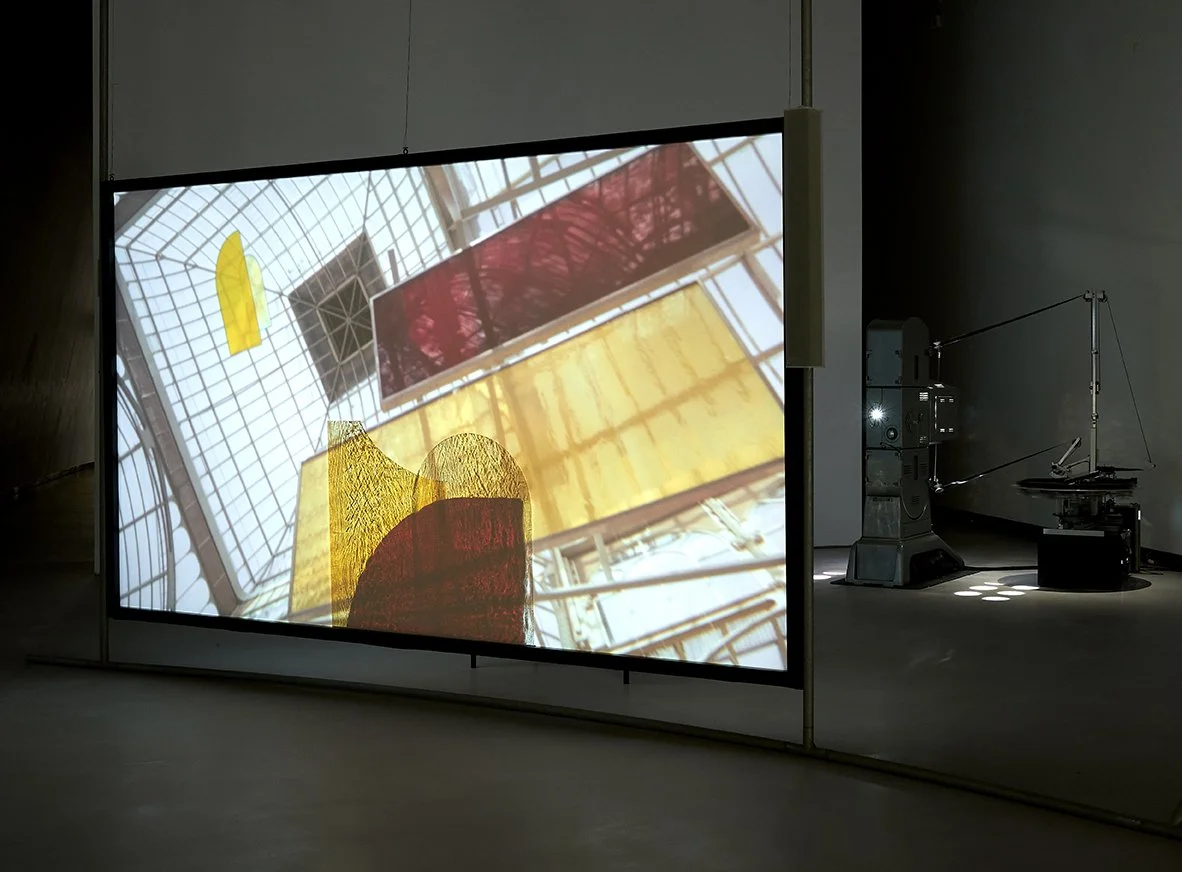

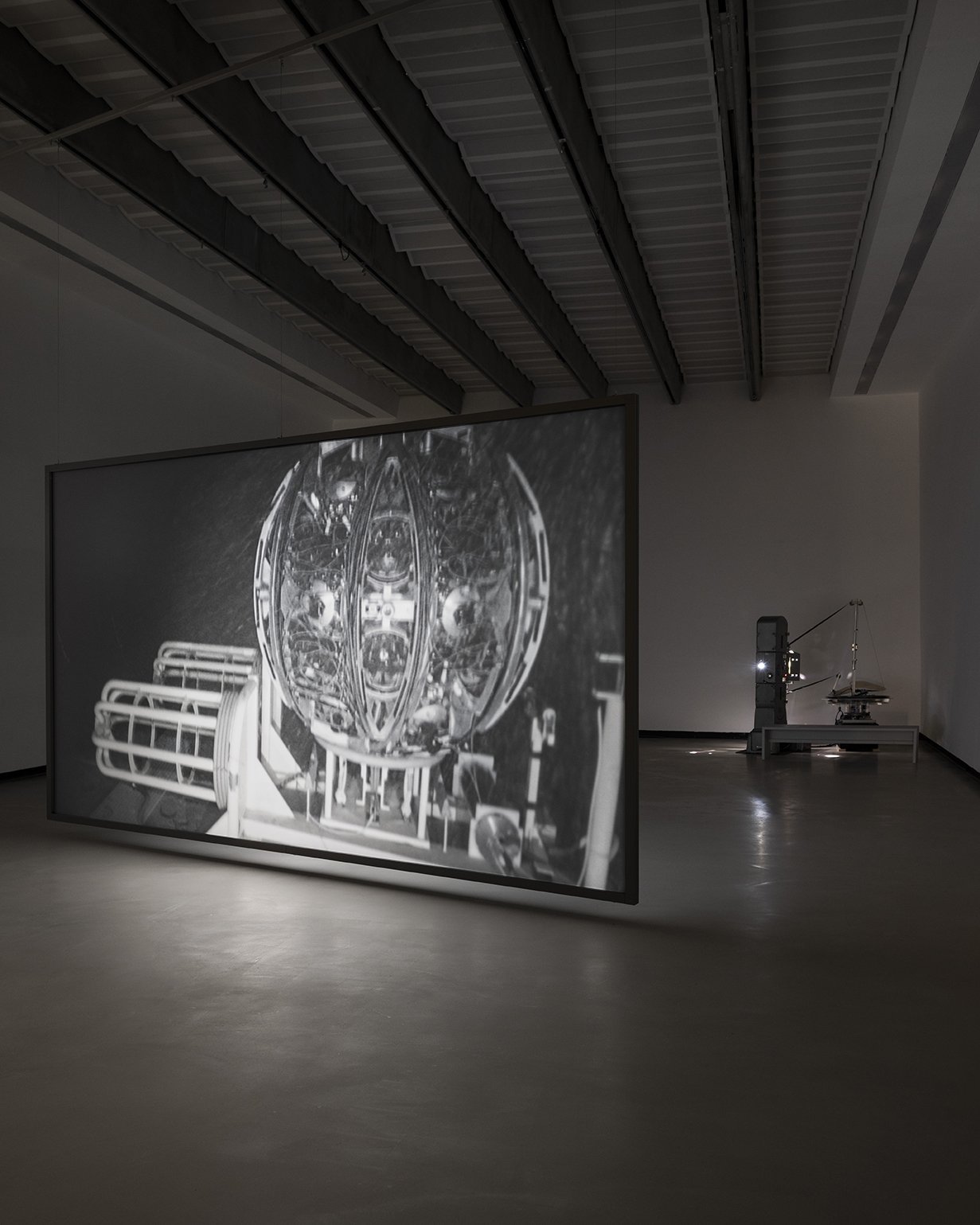

Rosa Barba “Frame Time Open” at MAXXI - Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Rome

Rosa Barba, Frame Time Open, image @Andrea Rossetti, courtesy of the artist, Esther Schipper, Vistamare.

Author: Michela Ceruti

Published Saturday, February 21, 2026

To step into “Frame Time Open” at MAXXI in Rome is to, almost immediately, feel that something in the surrounding proportions has shifted. The threshold does not simply separate outside from the inside; it recalibrates you. In a short video presentation, curator Francesco Stocchi speaks of Rosa Barba’s practice as an invitation to begin imagining. The phrase lingers because it sounds so gentle. And yet, the exhibition itself is anything but passive. The moment you enter, you feel shrunk and enlarged all at once – like a figure in a dream who has chosen the wrong, or maybe the right, vial and discovered that shrinking is a way of gaining access. The machines tower over the viewers; the beams of light slice through the air at improbable heights; the architecture stretches into a kind of speculative horizon. You are smaller, but you see more.

Barba’s works have always searched for cinematic effects outside of the screen; for cinematic edges, its underside, its architectural skeleton. Here, that search becomes spatial, like a railway track that cuts through the museum’s gallery, turning the floor into an axis of movement and anticipation. The railway track is not merely a prop but a force line, suggesting industry, travel, and the narrative that pulls forward. Around it, projectors stand exposed, their bodies solid and insistent. Nothing is hidden. Cinema is dismantled and redistributed: night, sound, celluloid, metal. The exhibition becomes an apparatus one can walk through.

Rosa Barba, Frame Time Open, photo @M3Studio, courtesy Fondazione MAXXI.

The title, “Frame Time Open,” reads like a three-word manifesto. The frame is the smallest unit of film, an indivisible particle of a moving image. Barba works with this infinitesimal measure not as a limit but as a building block, transforming strips of celluloid and obsolete cinematic devices into sculptures and installations. Time, in her hands, is not a neutral succession of identical seconds. It is thick, resistant, and material. It coils on the floor in loops of exposed film; it vibrates in the repetitive clatter of a typewriter striking letter after letter onto a blank 16mm; it stretches and compresses as reels turn in opposite directions inside a glass box. Time becomes something that occupies space. It has weight, tension, and elasticity.

If Andrei Tarkovsky once described cinema as “sculpting time,” Barba seems to take the phrase almost literally. And there is the word “open” in the title, referencing the artist’s refusal to closure, a field of possibility, the word suggests that neither frame nor time are fixed. Both could be expanded beyond their inherited definitions, beyond the traditional cinematic borders, and even beyond cultural categories themselves.

Rosa Barba, Frame Time Open, image @Andrea Rossetti, courtesy of the artist.

Barba’s approach is quietly subversive because it treats cinema not primarily as storytelling, but as a construction block. The projector is not a transparent mediator of images; it is a sculptural object and a performer. The beam of light does not simply reveal a narrative; it traces a path through the gallery, dividing it into volumes and thresholds. Light indicates where a story might be found, but it also undertakes its own journey, bending and dissolving into particulate haze. It is both a guide and a protagonist. In this way, light becomes sculpture –a passage within the narrative that is also a narrative of passage.

“Frame Time Open” gathers work from the past two decades alongside two new commissions: a 335mm film titled Myth and Mercury and a sculpture whose anxious declaration seems to echo through the space: They Are Taking All My Letters. Yet, these works do not assert themselves as isolated statements. They function more like nodes in a network. A film flickers in one direction while, elsewhere, thousands of metal letterpress blocks form a dense sphere, their arrangement following the logic of shape rather than alphabetical order. Language, once a tool of clarity and distribution, becomes cryptic and unstable. The obsolete letters –– freed from their utilitarian task –– suggest that meaning is never fixed, but always rearranging itself according to forces we do not entirely control.

Nearby, a typewriter performs a monologue by typing directly onto blank film, each letter projected as it is struck. The action is mechanical, almost indifferent, yet strangely intimate. The machine appears to write without pause, extending the time of production to the duration of each keystroke. Letters accumulate in tangled skeins of celluloid on the floor, a physical residue of thought. Watching it, one wonders where authorship resides. In the machine? In the code? In the rhythm of repetition? The process is entirely visible, yet the underlying meaning remains elusive.

Elsewhere, strips of film wind and unwind around discarded reels inside a glass frame, tightening and loosening in a continuous play of tension. The movement generates abstract compositions that recall painting, though nothing is fixed. These “cinematic paintings,” as Barba calls them, do not project images outward; they hold the image within the material itself. Here, cinema approached painting not by imitation, but by exposing its own support, its own skeletal structure. The celluloid is both surface and subject.

Rosa Barba, Frame Time Open, image @Andrea Rossetti, courtesy of the artist, Esther Schipper, Vistamare.

Because so many works operate simultaneously (projecting, rotating, typing, humming), it becomes difficult to speak of them individually. They conspire to create a liminal environment that resists the usual logic by which we divide time and organize space. In everyday life, we rely on these divisions. They reassure us. They help us accept our finitude by offering measurable units: hours, frames, rooms. In “Frame Time Open,” those units loosen up. The gallery no longer feels like a sequence of rooms, but like a single, breathing organism. Sound travels unpredictably. Light redraws boundaries. The railway track suggests movement without guaranteeing arrival.

This destabilization is not chaotic; it is speculative. Barba constructs a dimension where uncertainty becomes productive. By pushing cinema into architectural space and allowing its mechanisms to remain visible, she allows it to transform into a tool generating alternate temporalities. The works do not ask us to suspend disbelief. They ask us to recalibrate our beliefs altogether. What if time were not a line but a material to be folded? What if language were not stable but perpetually on the verge of rearrangement? What if a frame were not a border but a threshold?

As you move through the exhibition, your own body becomes part of this system. You adjust your pace to the rhythm of the machines, you pause where light thickens. You step over coils of film as if navigating the remains of an unseen event. The sense of being small returns –not as reduction, but as access. Reduced in scale, you begin to perceive the infrastructure that usually escapes notice: the mechanics behind projection, the physical labor of writing, the tension inside a strip of film.

In the end, what “Frame Time Open” has to offer is permeability. It leaves the frame ajar and time unsealed. To accept its invitation is to enter a space where categories dissolve, and imagination becomes a means to re-orient oneself. You emerge altered in proportion, aware that cinema is not confined to the screen and that light, sound, and matter can conspire to produce another order of experience, in which uncertainty is the generative condition of meaning.

About the author: Michela Ceruti is a writer based in Milan. She is the managing editor of Flash Art Magazine.