On Finishes. Wangechi Mutu: Black Soil Poems at the Galleria Borghese, Rome

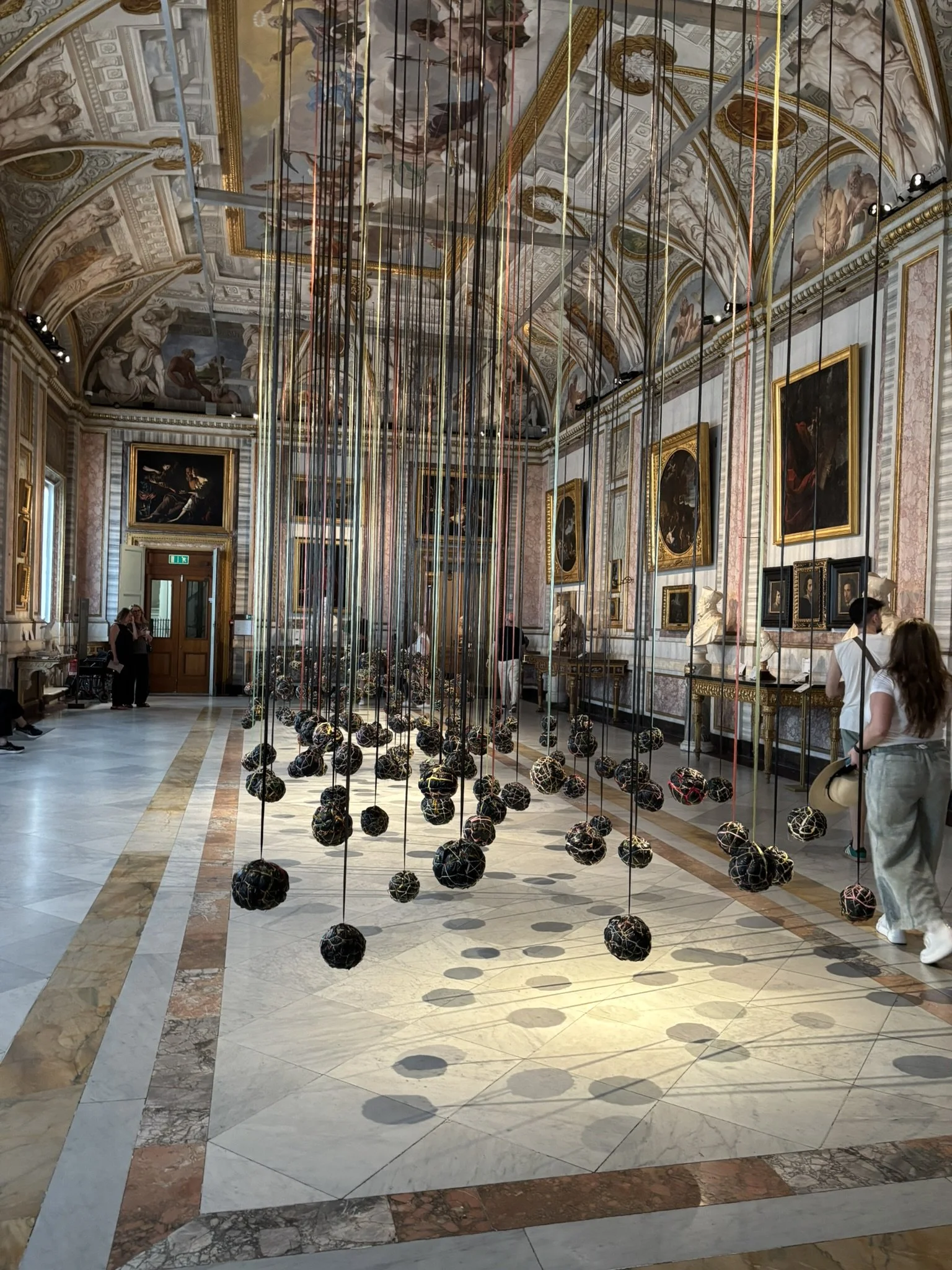

Wangechi Mutu, Suspended Playtime, 2008. Photograph by William Corwin.

Author: William Corwin

The saying goes “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em,” and the more insidious political corollary to that is to beat them by joining them: working from the inside, as it were. This is true as much in art as in politics, and Wangechi Mutu’s glistening, and sometimes dusty penetrations into the hermetic bubble of the Borghese Palace is a primer on how to, and how not to, work from the inside. There are marvelous works on the exterior, coiled snakes in the gardens, and two majestic female goddesses astride the entry to the galleria, The Seated I and The Seated IV (both 2019), but the more fascinating challenge was conquering the heart of the collection.

I had never been to the Borghese Palace before my visit this June, so I was initially impressed by the subtlety and understatement of the interior décor. I’m being facetious. The palazzo is a tribute to a monumental excess of luxury and materials: every surface inlaid with constantly shifting, vibrating patterns of exotic marble with gilt-bronze and writhing plaster detailing, every ceiling an overwhelming cacophonous fresco involving Laocoön-ic knots of gods and mortals, and almost every room containing a convoluted and technically perfect marble by Bernini. Mutu has chosen a strategy of intrusion rather than exhibition.

Wangechi Mutu, Older Sisters, 2019. Photograph by William Corwin.

What defined Mutu’s successful works in the exhibition was material and choosing to confront the histories embodied in the Borghese on their own terms. Outright confrontation failed to succeed, but it wasn’t based on content. In the Room of the Emperors, Mutu achieves exactly what she’s looking for. Placed on the mirrored top of an antique table, a pair of disembodied heads, Older Sisters (2019), in darkly finished bronze, are unmissable yet have assimilated into their surroundings. The gentle expressions, the closed eyes, and perfect coifs of the subject leave us to question whether these are decapitated heads or traditional memorials such as the well-known examples from the Kingdom of Benin, placed on their sides.

But the implied horror of a lone head is in perfect keeping with the stylized violence of Bernini’s indulgent Rape of Proserpina (1621-22) adjacent. From the ceiling, Mutu has draped necklaces of oversized beads –like the modernist necklace of an Italian countess—from the ceiling. While they are the direct contradiction, visually, of the classical dentilation (rectangular tooth motif) ringing the cornice of the room, they are a crisply geometric pattern of perfect black spheres, mocking the marble whiteness of the Bernini, the mythological friezes running under the cornice, and the pudgy putto flitting about this salon. It works, and we understand.

Wangechi Mutu, Poems By My Grandmother, 2017. Photograph by William Corwin.

Works such as Suspended Playtime (2008), or The Grains of Words (2025) or Bloody Rug (2022) are not ineffective, it’s just that in a tightly regulated ecosystem of materials, they don’t read as revolutionary but merely as transient and ephemeral, lost in an airless and frozen condition. Grains of words is a floor-sited text piece made of coffee beans, but this isn’t a space of text, the lives of the ultra wealthy are rarely intellectual or academic, and so it lacks presence in the space—it’s pearls before swine. The same is true of the abstraction of Suspended playtime and Bloody Rug, the former a sculptural installation of a multitude of hanging orbs with a very DIY aesthetic, and the latter an AbEx composition of red forms on an off-white background in shag carpet: Abstraction as a genre seems almost transparent in the Palazzo Borghese.

This is why Mutu is such a singularly good choice—her monsters, mythological female figures, and war and hunting trophies come out of a parallel tradition of mythologized wealth, power, and violence, simply transposed 2,700 miles southeast. The abstract tools she does utilize effectively in several works, such as the sublime and horrific Poems By My Great Grandmother (2017), of Horn and lusciously matte red mud, work because they integrate horror and the hunt: ideas mirrored in myriad scenes of rape and struggle throughout the galleries. As an indictment of the depravity and good taste of wealthy elites from Nairobi to Rome, Mutu’s installation is an adept Marxist gesture, but the Palazzo Borgese requires that one be very particular as to how those gestures are executed.

Wangechi Mutu: Black Soil Poems at the Galleria Borghese, Rome, on view through September 14.

About the author: William Corwin is a sculptor and writer based in New York. He writes for The Brooklyn Rail and ArtPapers and previously for Frieze, Canvas, Art & Antiques, and ArtCritical.

Wangechi Mutu, view of installation in the Salon of the Emperors, Palazzo Borghese. Photograph by William Corwin.