Hot Coffee Conversation with writer Igor Gelbach

Published Monday, December 29, 2025

When we are growing up, we are soaking up conversations all around us, from figures close to the family circle. We try to understand the discourse, and as we grow up, we hope to understand it better. Distinguished writer Igor Gelbach, who lived in Georgia, Australia, and now resides in Israel, has been such a figure for me. Closely connected to my parents and their ‘adult,’ sophisticated world full of references and allusions that I understand better now. Gelbach, alongside my parents, inhabited the most optimistic period of the Soviet regime, namely so called golden 1960s, when culture and science had certain clout amidst the dreary political, bureaucratic landscape, and when educated younger people hoped for different outcomes.

Igor Gelbach (b. 1943) is a Russian-language writer whose work explores memory, displacement, and the intersection of personal lives with 20th-century history. Trained as a physicist at Tbilisi State University, he lived across the Soviet Union—including Tbilisi, Sukhumi, Riga, Moscow, and Leningrad—before emigrating to Australia in 1989, later settling in Tel Aviv. Writing primarily in Russian, Gelbach has published novels and prose collections in Russia and abroad, with several works translated into English, including Confessions of a Clay Man, Blum Lost, and Tsaplin’s Testimony. His fiction is marked by intellectual density, historical layering, and a cosmopolitan sensibility shaped by exile and migration. Earlier this year, Gelbach published his recent book titled “The Latecomers or the Life of Richard Dubrovsky,” and it was a perfect chance to interview him.

Nina: Imagine you are in your favorite coffee or tea spot. Where is it? What are you drinking? What are the three things you see right now?

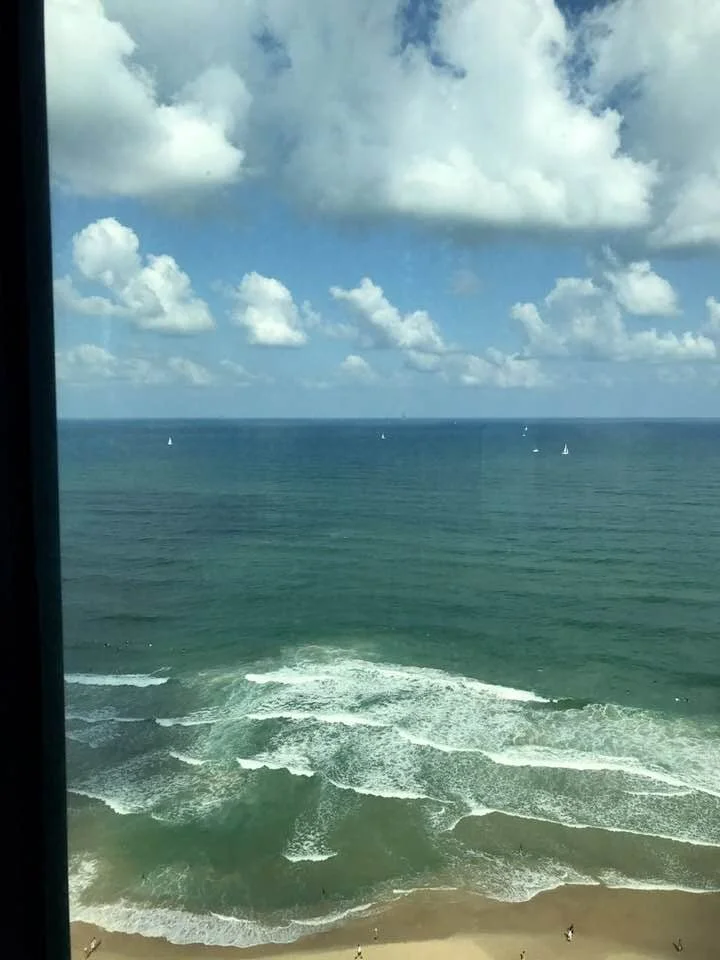

IG: In my youth, when I was studying in Tbilisi and occasionally traveling to the seaside in Sukhumi, I spent a considerable amount of time in a cafe located on the second floor of one of the piers. At the end of the pier is a yacht club, and from the cafe, visitors can see the sea, yachts, mountains, and the embankment. Approximately four decades have passed since I lived in Georgia. Since that time, I have lived in Melbourne, Australia, for 20 years. While there, I loved to have coffee on the long pier of the St. Kilda Yacht Club. For the last fifteen years, I have lived in Israel, in Bat Yam, a suburb of Tel Aviv, and every morning, I have the same Turkish coffee that I brew myself now. Outside the window are palm trees, the sea, and paragliders soaring above.

Nina: I just completed reading your latest novel titled "The Latecomers or the Life of Richard Dubrovsky," published by Palmyra. Among the many strands you interweave in this narrative, either directly or through allusions, references to plays and poems, the prominent one is of memory and its nature. A philosopher named Professor Wunderlich describes the historical, personal, and subjective nature of memory, using metaphors such as a palimpsest or a cloud, the latter carrying more religious connotations. Is memory a theme running through all your writing practice? Did your understanding of its mechanisms change over time, and if so, how?

IG: Memory is one of the most precious human assets and one of the most important tools of every writer. It seems to me that human memory, like everything else, is constantly changing and restructuring; some connections are born, some die. Some come back to life after a long slumber.

Speaking of "The Latecomers" written in Bat Yam, I can say that the very genesis of this text, which took many months, about a year, to write, is connected to the Georgian song of the same name, “Daigviane” which struck me. Actually, this song is an aria from Niko Sulkhanishvili's unfinished opera "The Little Kakhetian." This opera features an aria sung by a shepherd who laments his late arrival at the battle with the Persians on the outskirts of Tbilisi. The sound of this aria awakened several memories of life in Georgia and gave impetus to the development of a plot dedicated to the life of the main character, Richard, who spent his early years in Georgia, where he arrived from Berlin in the second half of the 1930s.

In that fateful battle for Georgia in 1795, the army of King Erekle II was routed, and Tbilisi was destroyed. "My path is tangled... Who am I, and who is my shepherd?" asks the shepherd. I must add that since the fates of the heroes of this novel unfold over several decades, and since the motivation for the actions of its main character is largely shaped by the enduring memory of his parents—who were forced to leave him in Tbilisi and travel to Mexico to organize the assassination of Trotsky—it seemed natural to emphasize this relationship to memory. I did so by introducing into the fabric of the novel the ghostly figure of another “latecomer,” Professor Wunderlich, who is attempting to develop his own original theory of memory.

Why do I call these people "latecomers"? It's worth remembering that very often our memory, interacting with the world in which we live, sets us up with certain goals that we try to achieve, but, alas, we often find ourselves late in this race. Of course, such thoughts don't come to mind right away, but only after years have passed. Having traveled to different countries and encountered different people and traditions, you inevitably begin to understand the extent to which people's behavior and destinies are connected to the culture that gave birth to them and, consequently, to memory.

Nina: I want to ask you about various cities that play a significant role in the novel, such as Riga, Sukhumi, Tbilisi, and a bit of Berlin. As a writer, you have also lived in many cities. Do you feel that their geopolitical or geosocial qualities influence the stories of the people who live there? In other words, could these cities be easily changed in your novel, or do you rather anchor your narrative around those cities, and the cities define the narrative and the people who live there?

IG: Well, of course, each of these cities is unique, each is interesting for its history and the established nature of the relationships between the people who inhabit them, and I probably wouldn’t write about people and cities with whom I am not familiar and have not established some kind of personal relationship. I lived in Riga for seven years, I finished high school over there, and spent seven wonderful years in Tbilisi, where I studied at the University and worked a little, and where I made wonderful friends with whom I've maintained relationships throughout these years, filled with various social and political upheavals. And I've been to Berlin more than once. And after the collapse of the USSR, many of my Riga friends ended up in Berlin and Vienna. I ended up in Melbourne, as I didn't want to wait for the collapse to begin in Sukhumi, where I'd lived for two decades. The only country I could settle in at the time, together with my sons, was Australia. So much of what I talk about in this novel is in one way or another connected with my experiences and impressions, communication with friends, travels, etc., and ultimately with the historical memory of which we ourselves are living witnesses and a part.

Nina: I am curious about your writing process. How long did it take you to write this novel? Was it something you had been planning over the years, or did it take shape within a short timeframe? Do you take notes on future novels? How do your heroes come together?

IG: I think working on every novel has its own unique characteristics. Sometimes it drags on for a long time, and what you're trying to create seems to gradually mature, acquiring new facets and twists, until you feel like you've seen the whole picture. And sometimes the whole picture suddenly becomes clear, as if illuminated by a bright flash of light. And this, of course, is connected, among other things, to the circumstances in which you find yourself, to what's happening to you and your surroundings, to what worries you and what you strive for—all of this, in some way or another, is present in what you write. But of course, there are also the demands of style, genre, and so on. And, of course, your memory and imagination play a huge role in the development of every novel, an alchemical blend of what you remember, what you know, and what you can imagine. Sometimes you can use your old notes, sometimes an idea strikes from out of nowhere. In general, the writing process includes some moments that aren't entirely conscious. And these unexpected shifts have their own charm... Sometimes you even feel like you've understood or accomplished something quite by accident. But more often, something comes about through a certain persistence and regular work on the text.

Nina: Who is your own personal favorite character in this book, if you have one, and why? Is he or she based on a real figure, or is it a composite figure from some people you have met over the years?

IG: If we are talking about "The Latecomers", then I must say that it is difficult for me to single out any one character; they rather exist in pairs: Richard's parents, Axel and Annette, with whom he lived in Berlin, as well as Richard's sister, Christina, and her husband, Oskar Greenfeld, who looked after him in Tbilisi. And finally, Richard and Ilona, his first wife—the three main couples whose lives are at the center of the narrative. And above this structure hovers the figure of Professor Wunderlich, connected to them not only by the historical period in which all of them live. Connection comes also by Wunderlich's theory of memory, and his acquaintance with Trotsky hunted by the NKVD. NKVD agents in the book include young Richard's father, his mother Annette, and, finally, Oskar Greenfeld, a confidant of NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria. That, in essence, is the structure of this novel, which tells the story of what happened to all these people and the world in which they lived.

Nina: At the center of “The Latecomers” are various people who, for one reason or another, have become hostages of specific historical circumstances, yet adhere to certain principles and values of patriotism, integrity, artistic truth, personal journeys, and honesty inherent in it. Do you feel that your own life and the life of your generation are a reflection of this trajectory?

IG: It seems to me that the characters I mentioned lived in a world that collapsed at a time when my friends, as I can’t speak for the entire generation, so my friends continued to actively participate in all kinds of generative activity, in science and culture. Compared to the characters in "The Latecomers," we have been simply lucky, perhaps in part because of our critical attitude towards the reality surrounding us and our unwillingness to fully integrate into the old system of relations, that is, to join the party, to engage in public activities completely controlled by the state.

Eventually, the Soviet empire in which we used to live collapsed, and a new reality arrived with its own dramas and conflicts that require and are awaiting their understanding and resolution, and this includes a reassessment and rethinking of much of what you’ve mentioned. At the same time, I believe that several values undoubtedly remain unchanged, although, in general, the world has become freer, and the concept of patriotism, for example, in the conditions of new freedom, has acquired additional dimensions. And this, perhaps, is the main thing, the hope that this process will not stop, although, as is clearly evident, from time to time monstrous relapses of the past occur in the world... And then it would not be a sin to remember the same question from the shepherd's song: "My path is tangled... Who am I, and who is my shepherd?" Perhaps this is precisely what justifies turning to the range of issues that I tried to outline in “ The Latecomers.”

Images provided by the respondent.