Hot Coffee Conversation with artist Rusudan Khizanishvili and curator Nina Chkareuli

Published Monday, January 5, 2026

I first met Rusudan Khizanishvili in the spring of 2015 through our mutual friend here in New York. In the following years, we have stayed in touch. Then, in 2017, we started to collaborate first on Khizanishvili’s exhibition at the Mark Rothko Cultural Center in Latvia, for which I wrote an essay, and then on the book “King is Female,” where I profiled Khizanishvili alongside two other Georgian artists, highlighting the larger narrative of the post-Soviet artistic and feminist identity. Since 2018, we have worked on numerous exhibitions, group and solo presentations, and interviews. Our latest collaboration is a current dual presentation, Sacrificial Rites, now on view at CAM Galeria in Mexico City, on view through January 25. This exhibition presents Khizanishvili’s paintings and drawings in conversation with the works of the well-known Mexican folk artist Chucho Reyes. I thought it would make perfect sense to talk to Rusudan again now, but this time mix it up a bit. Below, you will find her responses to my questions, as well as my answers to hers, along with the images we both selected to accompany our queries.

Nina: Imagine you are in your favorite coffee or tea spot. Where is it? What are you drinking? What are the three things you see right now?

RK: I would love to say that my favorite coffee spot is somewhere in the world — perhaps in Paris or Berlin — but in 2025, my favorite place is my home, in my living room. I wake up and ask my daughters or my husband to make me coffee with milk. I sit on my dusty-rose velvet sofa and drink my first cup slowly, sip by sip, without any rush, stretching the ritual for as long as possible. In front of me is a glass coffee table covered with books. Each morning begins with watching artist interviews or art documentaries — this is my daily ritual and the true start of my day. Next to the television stands an old antique Chinese cupboard, displaying a collection of ceramic sculptures. Some of them are my own works; others were collected during my travels to different countries, along with a few discovered at flea markets.

Rusudan Khizanishvili’s home, Tbilisi.

Rusudan: Imagine you are in your favorite coffee or tea spot. Where is it? What are you drinking? What are the three things you see right now?

NC: My usual coffee ritual happens at home. Around 8:15-8:25 in the morning, after getting the kids ready for school, I sit in a deep yellow armchair and look out the window. There’s bright morning light, trees not too far away reflecting the seasons through their branches, and a patch of sky. New York has a very particular blue — dense and intense, like the city itself. Right now, it is overcast, though. I drink my coffee and read a fiction book, then, saving research reading for later in the day, when my focus sharpens. I also try to keep my phone as far away as possible to set the right tone for the day.

This routine shifts considerably when I’m in other cities, and I enjoy that change. In Istanbul, for instance, I love strong Turkish tea, often drunk on streets lined with antique shops and old houses, or an elegant cup of tea in Lisbon. I also cherish a memory of a cappuccino on San Marco Square from a long time ago, when I was fourteen — after the rain, the dream that this city holds was sunlit and fresh, almost like a Veronese painting. Coffee, for me, is never just a beverage. It is a beginning, a spark, a sense of intention. It shapes the moment that always changes depending on the day, the place, and underlying dynamics.

A cup of hot tea in Lisbon, 2025.

Nina: What role does the notion of sacrifice play in your artistic practice?

RK: The idea of sacrifice in my practice is a symbol of transformation — the loss of something so that something new may be born. At times, this means sacrificing my own fears, painful memories, or personal space so that the work itself can gain life. In my view, sacrifice also offers a chance to rebuild identity by allowing a previous version of the self to vanish. It replaces inherited or harmful patterns and creates the conditions for renewal. In this sense, the necessity of sacrifice becomes a means of survival — a kind of saving mechanism, sustained by the almost phantom-like illusion of rebirth.

For me, this process is almost ritualistic — a disturbance of inner balance that is then transformed creatively. Sacrifice — substitution — is so deeply embedded in our genetic code that without this pattern, our existence in this given reality would probably be unimaginable.

I am also deeply interested in observing this process from the position of the viewer, in how our instinctive past collides with the digital present. Perhaps this very technological revolution will bring us closer to our origins rather than further away from them.

Still from The Sacrifice (1986) Andrei Tarkovsky

Rusudan Khizanishvili, The Shrine of the Gold, 2025

Rusudan: What does sacrifice mean to you, and do you think rewriting our own story — through life or art — is actually possible or helpful?

NC: To me, sacrifice means stripping away parts of identity that no longer serve one’s self to give space to the new roots, plants, and flowers. It has happened to me numerous times, and it has always been painful. I have shed a very safe and solid identity of a Georgian girl when immigrating here to the US at 21 as an international student. Then I was building an identity as a student and a worker in the field of international relations and social research. I have shed that identity when becoming a mother and concentrating on my young children for the next five years. Since they became older, I have been building my identity as a professional in the arts as a curator and as a writer. Building this identity requires sacrifices too, although I cannot and will not sacrifice wellbeing of my children to professional success.

I would not have rewritten my life if I could; it has been a meandering road, but I am grateful for its every turn. It showed me people, life, values, emotions, philosophies, structures, and countries from very different perspectives, and without this, I would be poorer as a person, as a researcher, or as a curator. What is painful about this process is that I have always put all my effort, trust, and drive into every single step of this journey, and sometimes had to break the road up to then start again, like Sisyphus, but in a different direction. Probably, this is my karma :)

Titian, Sisyphus, 1549.

Nina: Where do you see any intersection with Mexican visual culture, if any?

RK: I sense a closeness to Mexican visual culture through its symbolic depth and its coexistence of life and death. The energy and colorfulness of Mexican art often resonate with my inner emotional states. As in Mexican art, emotion and mythology intersect in my work as an integral part of both everyday life and spiritual experience.

I often observe Mexican gods from a distance and try to recognize our own, Georgian gods within them — or, conversely, I place them in opposition to one another. Perhaps I will understand this better after visiting Mexico. We have spoken before about recognizing gods — how “ours” or “foreign” they truly are, and how we search for them within our own cultures.

There is something profoundly paradoxical in this search for dead gods — gods humanity has killed multiple times and resurrected just as many. And yet, we can never fully replace the void created by the destruction of a god, so we return to them again and again — only for them to return more brutal than before.

The Deer Dance, or La Danza del Venado

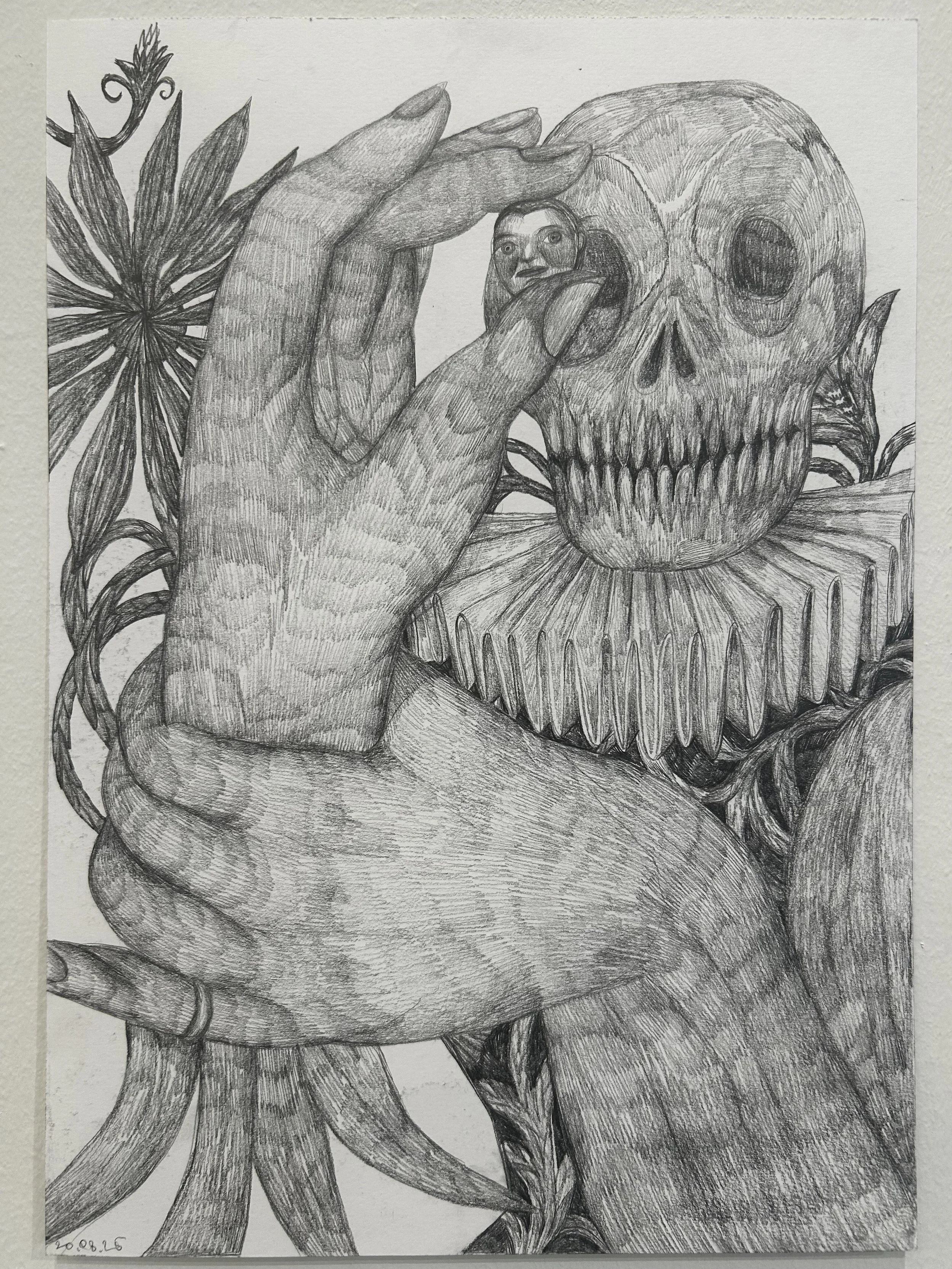

Rusudan Khizanishvili, Midnight Drawing series,2025.

Rusudan: What kind of work genuinely excites you lately, and is there anything you’re a bit tired of seeing everywhere right now?

NC: Lately, I have been sensing even more than before that I am gravitating toward the art that prioritizes the atemporal quality, a non-specific rhythm, having attributes of going further in the way of understanding who we are as individuals and people. Asking questions and finding answers while not being limited by a given historical moment.

What shapes us?

What are our recurrent questions?

How are these questions formed?

What makes us into who we are becoming?

Perhaps it has something to do with the years going by and my need to reappraise what I have been doing.

I have found that many of the questions I have been asking before were tied to the question of power, or rather imbalance of power, framed within a colonial, historical, or narrative structure. These frameworks are powerful and valid, and I am still very much interested in them, but larger human questions are becoming more prevalent. For example, as history shows us, an excess of power breeds totalitarian approaches, it breeds corruption, it breeds hate, and fragmentation. How does this affect artists? Who are they becoming? Who were they becoming during the Soviet regime, for example? I am interested in seeing art that either directly or indirectly is connected to these questions, but on an individual scale, and as we are collectively continuing to exist in the world of global political turmoil, these questions are once again heartachingly important. Having conversations about this is important, and this is why I am putting so much energy into this platform.

I am tired of seeing boxed-in, pre-packaged narratives that cater to the objectification of the body and the mind. The single most valuable dimension of art and culture is a non-linear richness of perspectives they offer; why would anyone want to reduce this to a single set of interpretations and ways of seeing? Art also meets where we are. Sometimes we need a jolt, and sometimes we need comfort, but none of it has to be one-dimensional or predictable.

Gregory Crewdson, Untitled, 1999.

Nina: Symbolism is of importance to you. Do you feel that certain symbols you have used have shifted over time?

RK: They changed together with me, as we grew up together. Sometimes the same figure — an animal or a body — takes on an entirely different meaning depending on my emotional or spiritual state.

Or they simply evolve: for example, hands, shoulders, and palms grow or shrink over time, acquire nails or claws, or become covered with fur.

Earlier, I chose symbols more consciously; now they seem to appear on their own — as intuitive signs emerging from within me, forcing me to speak their language. I often feel as though I am enclosed within a triangle — myself, the painting, and the story. Sometimes the work is born independently of me, and when it is finished, I read it as if it were a book. In that moment, I try to decipher the meaning of its signs — or leave that space of recognition open to others. I have also come to realize that the visual language I use, which I once believed to be naturally understood, reveals itself much later — even to me.

At times, the symbols that appear in my work are more precise, more predictive, than my own conscious awareness allows me to grasp. Meaning unfolds over time, often beyond the moment of creation.

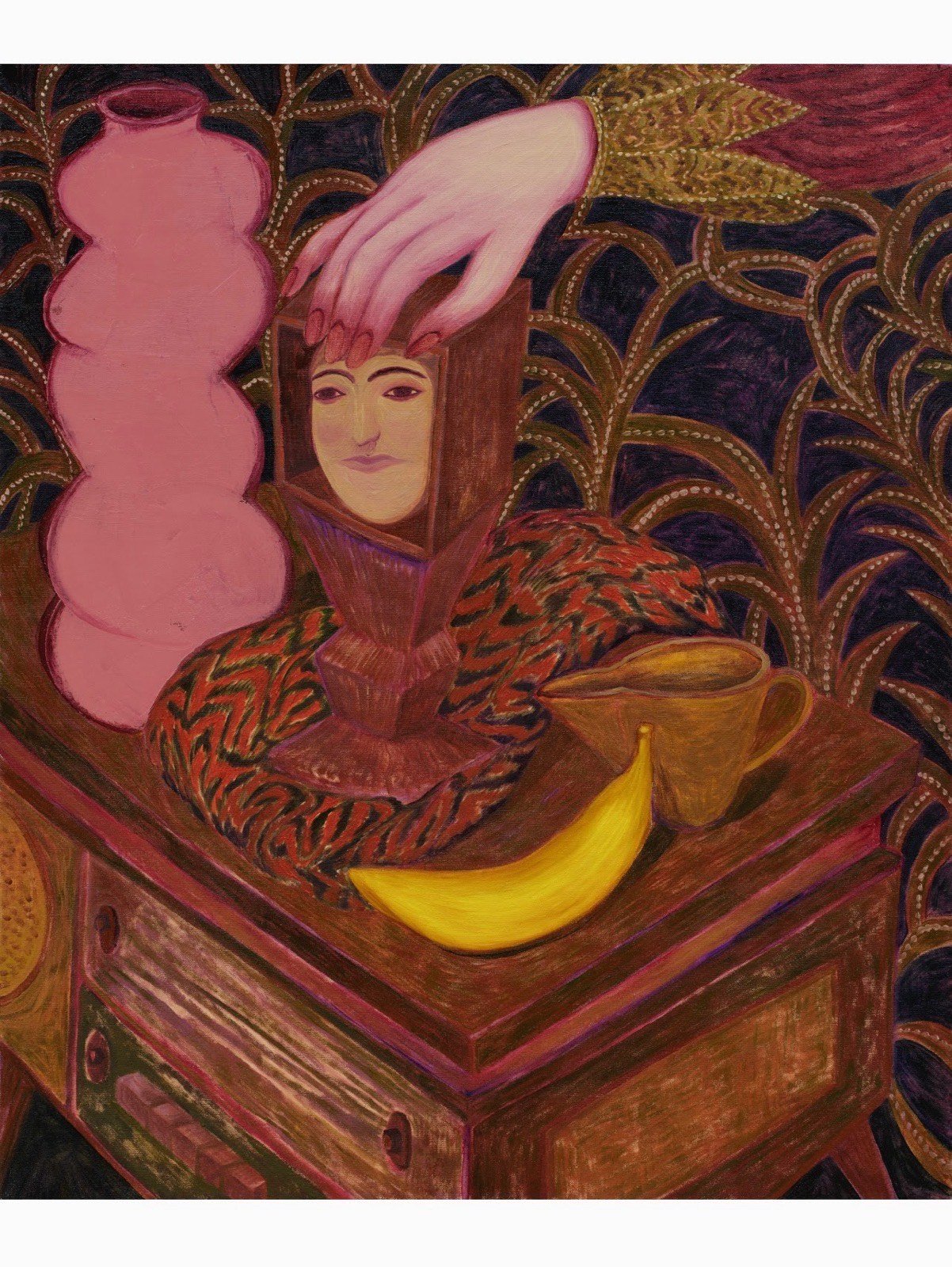

Rusudan Khizanishvili, Pandora, 2024.

Rusudan: When you walk into a show, what makes you immediately trust an artist—and does that change when the artist is someone you’re close to?

NC: I trust the artist if their life story either lines up with their work or is completely at odds with it. For me, a biography of an artist, their roots, training, references, research, and motivation are as important as what I see on display. Joseph Beuys would not have done what he did without his story, nor would Giorgio Morandi or Elene Akhvlediani. But on the opposite side of the spectrum, Lucian Freud lived a life that was completely at odds with his cold, analytical, masterful dissections on canvas. Just as Georgian sculptor Tamar Abakelia portrayed women who were living a much more ideologically and labor-driven life than she could have as a victim of the Soviet regime. I am a process-oriented curator, and the process I have in mind is the life of an artist. While the modernist fluidity and stream-of-consciousness method matter to art, I do believe that their purity is the result of the larger life processes.

I also look at how artist handles time in their work, how it affects them, or how it is reflected in what they do. Either historical time, the time it takes to create a body of work, or the time it took them to form their artistic identity.

I would not say that these two dimensions, time and process, change depending on whether I know an artist or not. I believe it is my responsibility to be objective and honest, and if needed, outspoken about this. Yet, when you know an artist, you also know the details and symbolism and progression, so this helps you to see things more clearly.

Lucian Freud, Larger Interior, W11 (after Watteau) (1981-83).

Nina: Please tell me more about the notion of the sacrificial lamb we have discussed over the years.

RK: The “sacrificial lamb” is, for me, simultaneously an image of innocence and spiritual strength — the figure of offering as the most virtuous and vulnerable being. It endures pain so that something greater and purer may be born.

Sometimes this lamb reflects my own inner state; other times it appears as a character in my works. Within this symbol, I see the unity of innocence and sacrifice — a silence that transforms into strength.

I would like to return here to a childhood memory: when I was a child in the North Caucasus (where I was born and lived until 13 years old), lambs were slaughtered in our large courtyard to commemorate deceased neighbors. The meat was then cooked and distributed, along with sweets and bread, to every family in the neighborhood. This ritual left a deep imprint on my memory and became the foundation for many reflections and emotions.

Lamb - was a face of mourning, a face of the unknown, a face of vanishing. This is my first lamb. The second lamb comes from the book — and later the film — A Story of Human Sadness by the brilliant Georgian director and writer Goderdzi Chokheli, where one day death descends among people, yet no one dies, and even the beheaded lambs remain alive. This is my second lamb.

My third lamb arrived to me only in the final year.

Rusudan Khizanishvili, Mandragora's Dream, 2021.

Rusudan: When you’re not “being a curator,” what kind of art do you look at purely for pleasure, without thinking professionally?

NC: I go to the Met or the Frick Collection and absorb with great pleasure the works of old European traditions. It is something that brings me an aesthetic boost, a sense of purity, mastery, and an ideal we all aspire to. It also has a connection to an earlier time when, as a teenager, I had a chance to visit great European museums with my father; those visits have formed my aesthetic sensibility.

Jean Baptiste Siméon Chardin, Still Life with Brioche,1763.

Nina: We spoke about this over the years, but with all the dynamics and shifts taking place in Georgia and in the world, where do you see the role of the artist today?

RK: Today, I see the role of the artist as that of a witness rather than a commentator. In a world saturated with speed, noise, and ideology, the artist’s task is not to explain reality but to slow it down — to hold space for uncertainty, contradiction, and silence. Art cannot repair the world directly, but it can prevent us from becoming numb.

It keeps memory, sensitivity, and vulnerability alive.

At this moment, my beloved country of Georgia is going through one of the most difficult periods of the past decade. My heart bleeds every day, and it requires immense effort to continue working and to grow stronger through creation.

In times of hopelessness, the mission each of us carries must itself become a source of strength. The artist absorbs collective pain and transformation and translates them into a visual language that can be felt rather than explained.

Perhaps today the artist must become a giant — not in scale, but in endurance. A guardian of the source: of memory, consciousness, and inner truth. In a fractured world, this act of witnessing is not passive; it is a form of resistance, care, and quiet responsibility. Like a Phoenix, the artist burns each night in the face of injustice, yet must be reborn every morning to continue creating.

Adigeni, my Motherland village, Southern Georgia.

Rusudan; If you could curate a show with zero limitations, what would it look like, and is there a past exhibition of yours you’d completely redo with that freedom?

Nina: Well, of course, it is any curator’s dream to have this type of freedom. If I had a zero limitation, I would take a single historical functional building, maybe in Georgia or in an abandoned palazzo or another place marked by historical trauma, and divide its rooms into segments. The overall idea of the exhibition would be to look at how art processes power. I would exhibit works by artists from the Middle Ages to look at how the church and its patrons shaped what we see. I would bring in works from the time of the Enlightenment, maybe in the form of artists performing plays of Voltaire or reading from Jan-Jaque Rousseau, to see how human reason has taken precedence over nature – a form of power we now fully see in our climate change. I would bring in works from the pre-Communist period of Eastern Europe, Socialist Realism, and post-Communist discourses. And one of the last rooms will have robot dogs roaming a post-apocalyptic landscape or a room from Tarkovsky. More than one room will have works by female artists to show how they are breaking through the power hierarchies. One final room will be devoted to the reflection on how art can fight back.

If I could redo one exhibition within this larger framework of the power and artist, it would be Trust Issues from the spring of last year in Berlin. Your works were part of this exhibition alongside the paintings of Gonzalo Garcia and sculptures and drawings by Saelia Aparicio, and all of you contributed to the discourse of parameters of trust, coercion, fluidity, and openness. I would add more works by all of you, while adding selective political, historical, and cultural information from your countries, thus expanding on the question of validity, critical thinking, and filtering what we consume.

Abandoned sanatorium, Georgia. 2022

Rusudan Khizanishvili, Portrait, 2023.

Berlin,2024.