Building Models: The Shape of Painting at the Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation

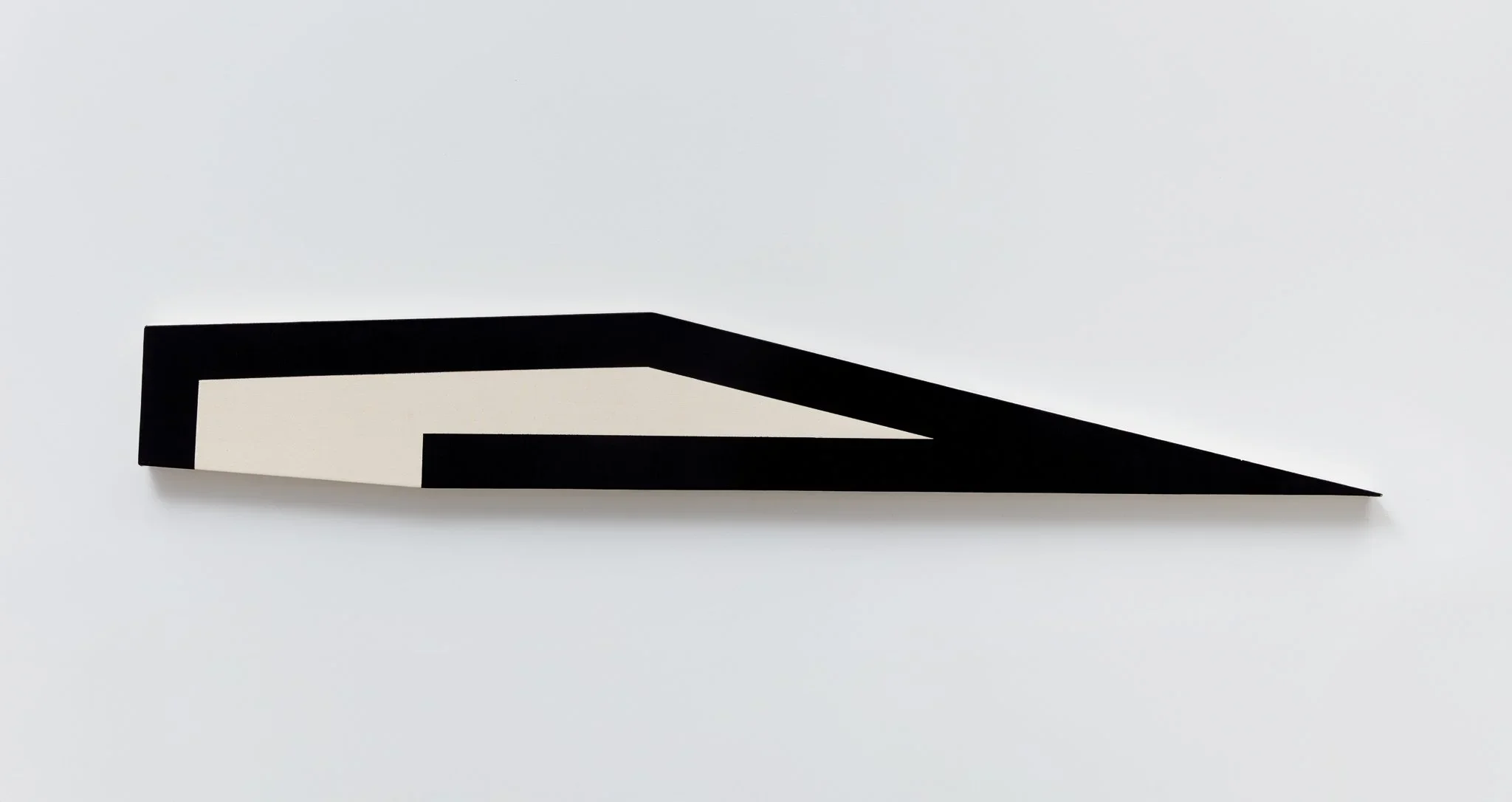

Ted Stamm,5ZYB-001 (Zephyr), 1982. Oil on canvas, 13 x 90 inches

Collection of Svetlana Zueva. Image courtesy of the Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation.

Author: William Corwin

I do hate blunt tautologies in history, but it is largely true that because artists started painting on canvas stretched on wooden frames, the imagistic depiction of space was normalized to a great extent. Canvas began to be used as a medium for paintings in the mid-fifteenth century, and from that point, up until Kandinsky, the painting was a rectangle, and an artificial window of sorts—we were always looking at an image, rarely a literal thing. Before that, in wall paintings/carvings and even wooden panel paintings, artisans felt empowered to fuck with the viewer’s perception and their sense of their own presence in space. For example, ancient Egyptian combinations of text, image, and architecture are as radical as anything Jenny Holzer or Joseph Kossuth has ever made. Saul Ostrow’s exhibition, Building Models the Milton Resnick Pat Passlof Foundation, is here to set us straight in terms of what painting is capable of, via the shaped canvas.

There are ten painters in this exhibition, and Ostrow pairs each artist with a conceptual motif that he feels the shape of that particular canvas is capable of expressing. Because the notion of artifice has been removed, a whole different set of rules of engagement with the art object is in effect. Ted Stamm’s piece 5ZYB—001 (Zephyr) (1982) resides close to the floor—the idea of centering an artwork on the floor at eye level no longer seems a requirement in Stamm’s piece, which also plays with the illusion of distortion—has the painting been crushed? No, it is simply that shape. Harvey Quaytman’s Paleologue (1969) also seems to have gained some internal kinetic fluidity: a pair of L-shaped canvases reject the pictorial as one L-nestles limply inside the other—fooling us with an illusion of flexibility rather than space. The same is true of Ron Gorchov’s Spice of Life II (2007), which bulges in an arc off the wall. I’ve always thought of Gorchov’s paintings as shields; the three-dimensional space contained behind the work seems reserved for an ancient presence or spiritual force. Gorchov’s work also noticeably casts a shadow, which is far less noticeable in rectilinear paintings. Gwenaël Kerlidou’s Pinwheel (2024-25) casts an artificial shadow, painted directly on the wall behind the painting, which forces the viewer to acknowledge both the artificiality of surface imagery and the physical presence of the canvas. Kerlidou and Joanna Pousette-Dart relate their imagery to the overall exterior shape—the long boat-shaped forms in reds, beiges, ochres and white in Pousette-Dart’s 3 Part Variation #2 (3 reds) (2015-16) are reflected in the three lobes of her canvas refuse to create an illusionary image and instead conjure an illusionary form—horses of very different colors. Li Trincere’s Red Checkmark (2011) seems to slouch comfortably in her white triangle canvas case: the painting is reliant on the stretcher shape in a perverse reconfiguration of the picture plane.

For the other artist’s the balance between surface and form becomes more of a delicate balance, and we become increasingly distracted—in a good way—by what transpires on the canvas as much as the shape on which it is contained. The drippy flows of color on Joe Overstreet’s Untitled (1982) don’t necessarily need the irregular trapezoidal construction of the canvas, but they leak out onto the extended stretcher bars, showing the freedom granted to the paint by non-conformist canvas construction. David Row’s yellow grid on a gray background also gently adjusts itself to an irregular Heptagonal substrate in Phantom (2022)—the orthogonal grid doesn’t jive with the canvas’ shape, but almost as an afterthought, a carefully placed steep diagonal connects the top and bottom nodes of the stretcher, offering a compromise between surface and support. Ruth Root and Russell Maltz are the two artists who hang as an act in itself. Root’s Untitled (2025) is simply the fabric alone, flat to the wall (minimal shadows), a layer of pattern laminated onto the room rather than offset from the wall. In contrast, Maltz’s S.P./ACCU-FLO (2013) is the opposite, and the only piece to not use canvas or another fabric, as it is all support—four plywood sheets dangling from a single point on the wall. The sheets are each neatly emblazoned with day-glo orange rectangles, as if to certify that a painting is definitely present, but while dallying with Suprematism, Maltz’s constructivism is more inclined to make us think about the plywood sheets and their physicality—as with all these works, composition is something that just happens, whether you try to force it or not.

About the author: William Corwin is a sculptor and writer based in New York. He writes for The Brooklyn Rail and ArtPapers and previously for Frieze, Canvas, Art & Antiques, and ArtCritical.

Installation view Building Models: The Shape of Painting at the Milton Resnick Pat Passlof Foundation, September 5, 2025 – January 17, 2026. Photo courtesy of the Foundation.

Joe Overstreet, Untitled. Acrylic on canvas construction, 84 x 88 inches© Estate of Joe Overstreet/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York; Courtesy Eric Firestone Gallery.