The God of the Bay of Roses: Living Mythology at Main Projects, Richmond, Virginia

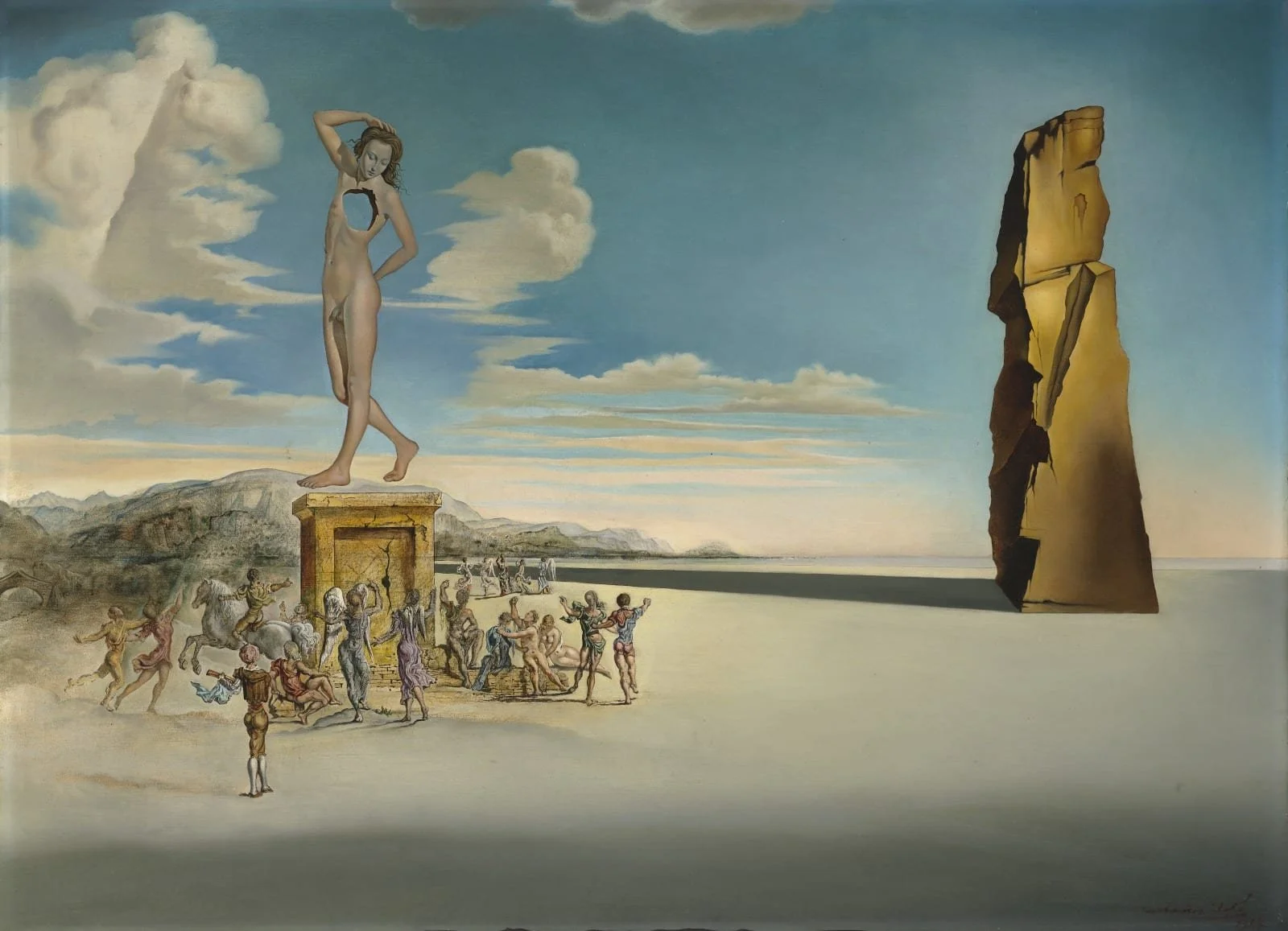

Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904–1989), The God of the Bay of Roses, 1944, Oil on canvas, 22 1⁄8 × 30 3⁄16 in (56.2 × 76.7 cm).Signed and dated lower right, Salvador Dalí / 1944 Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Gift of the Estate of Hildegarde Graham van Roijen, 93.111. Photo: Katherine Wetzel © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Author: Murph Phi and Irini Goudas

The God of the Bay of Roses arrived at Main Projects with a confidence rarely seen outside major art capitals, unfolding with a sensitivity deeply attuned to art history. The exhibition is anchored by Salvador Dalí’s 1944 painting with the same title, which is held in the collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts nearby. The God of the Bay of Roses does not treat history as a fixed authority, but as a sprouting, living source of inspiration. Completed during the time of Dali’s American exile, the work mirrors a moment when Surrealism was not yet fully digested by broad audiences. At that time, as US institutions absorbed such works, they often misrepresented the movement, a contrast that was successfully highlighted in the exhibition.

Dali’s painting represents a slim, masculine figure with the head of his wife, Gala, in an open, dreamlike landscape. Its multitude of potential allegorical interpretations renders the painting a fertile ground for the genesis of new artistic expression. The show features works by 18 different artists, where themes related to desire, mythology, fractured identity, and the human body are extensively explored, expanded on the themes present in Dali’s painting. Works in the exhibition similarly exude the sense of the uncanny, so much exalted by the Surrealists, proving that surrealism’s visual vocabulary is relevant to contemporary anxieties.

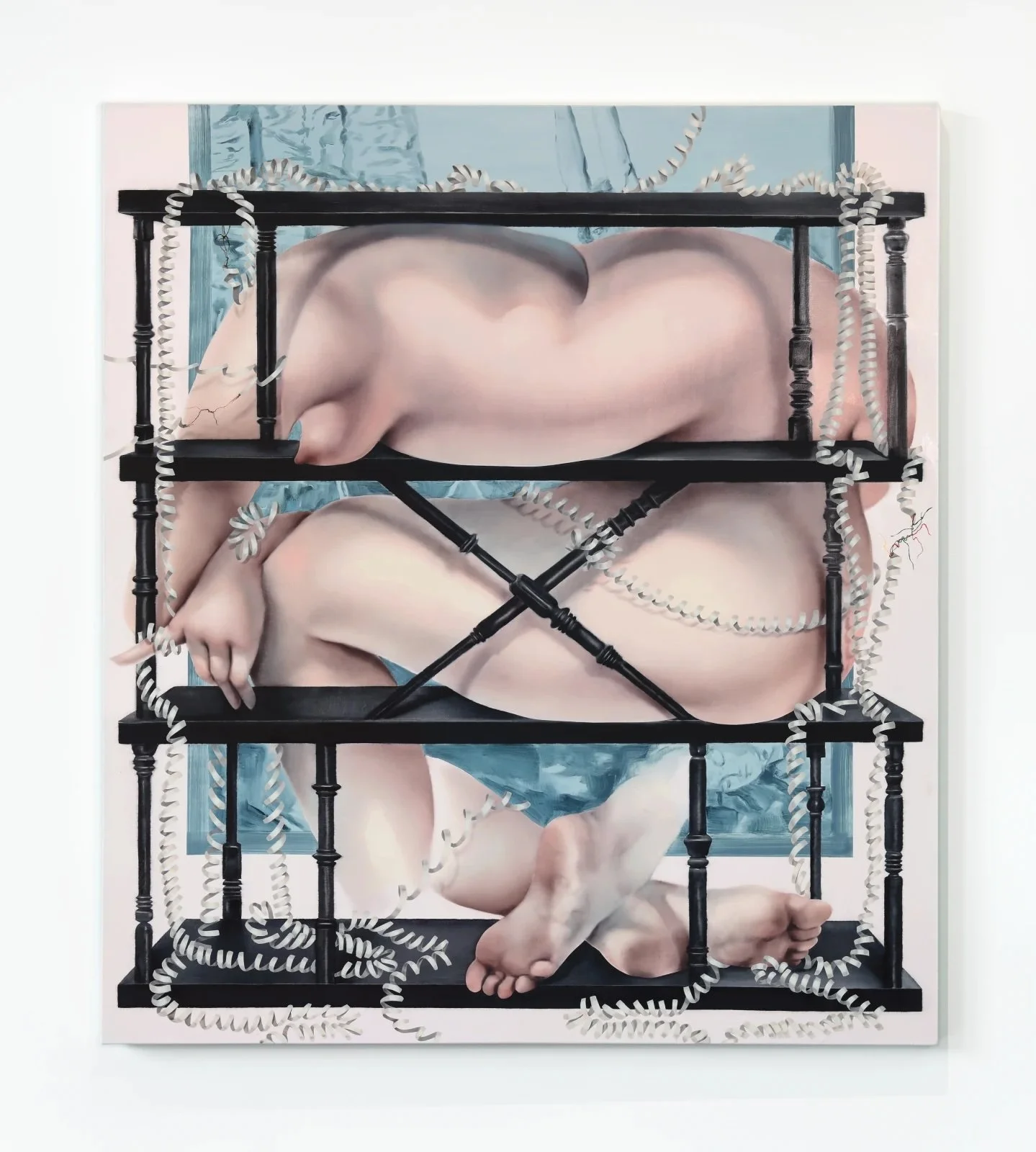

Meghan Stevenson uses the body in a way that explores its essence as a conduit for the mind. Her work, The Headless and The Heartless, features the back of a female figure with a hollow center that has clouds, a direct reference to the clouds in Dali’s work, transforming the image into a symbol of introspection. Sarah Slappey’s Shelf Squeeze aligns with the exhibition’s curatorial logic by translating Dalí’s psychic fractures into the terrain of the domestic interior. Like The God of the Bay of Roses, the work holds desire, vulnerability, and power in a single frame, relocating surrealist tension from mythic space to everyday architecture, where control and intimacy quietly unfold.

Other artists in the exhibition, like Marisa Adesman and Arghanavan Khosravi, channel subconscious awareness through the body, focusing on the inner workings of the mind. Landscapes are also echoed throughout the works in the exhibition. Kat Lyons, Ginny Casey, Katherine Bradford, and Ryan Driscoll focus on landscape as a metaphor for internal architecture, while others provide a more direct homage to Dali’s treatment of the theme as a place for reflection on the sublime and on mythology. Mythic presence is also directly alluded to in the sculptural works of Kim Dacres and the painting of Umar Rashid titled “GOD OF THE BAY OF ROSES REMIX FEATURING LAS AMAZONAS CROMADAS, HOMBRE DE ORO, Y EL REY MINOTAURO,” 2025.

Rather than presenting Dalí as an untouchable locus of reference, curators ot the exhibition, EricThomas-Suaell and Laura Martin Mills, open up his practice, reflecting how the multiplicity of Dali’s meanings, along with visceral responses, permeate contemporary artistic practices. The ambitious curatorial framework demonstrates how the core of Surrealist practice is articulated across painting, sculpture, and hybrid forms, with participating artists engaging the movement’s psychological architecture with notable fluidity. Dalí’s symbolic fractures, in this reading, are reactivated as contemporary concerns through present-day formal and conceptual translations

The success of the show at Main Projects lies in its resistance to flattening responses into a single thesis. Instead, the curator embraces a multiplicity and diversity of iterations, allowing perspectives to flow seamlessly with their original references. Each artist exists autonomously, yet collectively the ensemble translates Dalí’s surrealist logic into a polyphonic field. These circumstances then allow beauty to coexist with disquiet, while the element of fantasy submits to a focus on contemporary instability - political, social, and by extension, existential. The result is a homage that seizes friction, and within that friction, the exhibition finds its grounding.

On the opening night, Michael Taylor, Director of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, offered a lengthy monologue that situated Dalí’s painting and the exhibition within a broader art historical and institutional framework. The evening ended with a dinner for collectors, artists, and friends of the gallery, providing the opportunity for sustained social and intellectual engagement with the complex topics the exhibition touched upon; a breath of fresh air in Richmond, a small yet pungent art city, which is in search of moments where conversations can extend beyond the gallery space, building curatorial literacy alongside community.

As Main Projects and other galleries of comparable stature enter smaller or mid-sized markets, familiar anxieties often arise amongst gallery owners and the community. One of these anxieties relates to the refrain that “the art is too high.” Yet this perspective overlooks how such galleries actually function. Alongside major works, Main Projects offers editions, publications, and literature that provide accessible points of entry, encouraging learning – the most beneficial and, perhaps, authentic of collecting behaviors. Under this dimension, the gallery’s ambition does not inherently exclude; it can instead raise the bar while opening doors of perception for the people daring to actively engage with the gallery’s program.

Another hesitation centers on the intimidation of proximity to a “big name.” One might worry that such juxtapositions can overpower the lesser-known artist on display. However, so do these assumptions collapse after a glance at the display itself. The gallerists behind Main Projects, Laura Martin Mills and Eric Thomas-Suwall, are not only seasoned collectors but also actively and generously advocate for the artists they support. Their deep understanding of art, accompanied by an open mind and curiosity for new works, encourages a safe environment where emerging and mid-career artists are provided with a platform. In this environment, the audience is encouraged to take a similar approach, grounded in curiosity. What’s unfolding from Main Projects is then a dialogue, an exchange, rather than structures that imply hierarchy.

Staged in Richmond, with Dalí’s The God of the Bay of Roses held just blocks away at a major institution, the response makes a quiet but firm statement that contemporary discourse is not exclusive to global capitals. It can take root wherever ambition and care are present. Main Projects does not arrive as an imposition on the local scene, but as a catalyst — one that sharpens the conversation and invites deeper participation. Additionally, The God of the Bay of Roses is less about revisiting a single historical masterpiece than about testing what it means to inherit and transform a visual legacy. The exhibition stands out because mythology is far from being crystallized, but is something we must continuously renegotiate. In that sense, the show feels not only timely but a necessary reminder that serious art, when thoughtfully presented, can expand all possibilities.

About the authors: Murph Phi is an art writer and director whose work sits at the intersection of cultural identity, placement, and intellectual exchange. His writing traces how meaning is shaped through institutions and the quiet politics of everyday survival and ambition.

Irini Goudas is graduating from a Master’s program in Art Business at Sotheby’s Institute of Art, where she wrote her thesis on the cultural phenomenon of Japonisme in Paris, with a particular focus on the work of Kitagawa Utamaro and his influence on late nineteenth-century art. Her professional experience spans gallery administration, curatorial practice, and art advisory.

Julie Curtiss, A Room with a View, 2025. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 20 × 25 inches. Copyright of the artist.Image courtesy of the gallery.

Sarah Slappey, Shelf Squeeze, 2025. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 55 x 49 in. Copyright of the artist, image courtesy of the gallery.

Sarah Peters, Augur,2022. Bronze with silver nitrate patina, 18 1/2 x 16 x 13 in. Edition of 3 plus 2 AP (#2/3).Copyright of the artist, image courtesy of the gallery.